Notes for an Epilogue

2010-2015

essay and texts by Eszter Szablyár

hardcover, 160 pages, 69 plates

34.5 x 28 cm / 13.6 x 11 inches

published by Hatje Cantz, Berlin

The most severe dictatorship of Eastern Europe ended with a spectacular execution at Christmas 1989. The hurried yet theatrical scene was broadcast live by the world’s news media – the ruthless death of the uneducated shoemaker’s apprentice-cum-dictator, Nicolae Ceauşescu, along with his wife Elena, who shared his cult of personality, was of symbolic importance. The elimination of the communist regime, developed from 1965 to the 1989 revolution, which pursued a friendly policy towards the West, yet later became isolated following the enforced repayment of western loans, left only promises of democracy in a country which was completely exhausted, both intellectually and economically. The revolution set the systematically impoverished society serious tasks, while an opportunity to interpret the past opened simultaneously with reconstruction. The burdensome legacy of the past decades waiting to be analyzed has included the image of areas covered with reinforced concrete factories as a result of aggressive industrialization, the memory of the central determination to eliminate villages and transform the village experience, with its traditions and agricultural way of life, into an existence in housing estates and slums characterized by empty shops, and the traumas of rationing embodied in endless queues and starvation. The political changes put an end to the period of intellectual terror as well as the infinitely prolonged physical misery. They involved a decision to halt the persecution of minorities and religious communities, to rein in the secret police, which, reflecting the paranoid system, kept an eye on everything, to close down political prisons operated as centers of ideological re-education, and to do away with the prohibition of abortion. However, the euphoria of change has been replaced by the silence of disappointment and the feeling of being let down. Romania joined the EU in 2007, yet today unemployment represents a serious problem, as does migration and the resulting complete depopulation of villages, as well as industrial regions turning into crumbling ghost zones.

The traditions of several centuries and the remains of the communist dictatorship’s decades are disappearing in parallel. This double passing is rendered by our photographic essay and text based on interviews and descriptions made on location. During our joint work of five years we have constantly experienced the compelling force of the final moments. The factory buildings we encountered a few months ago no longer exist, Ceauşescu’s princely bed and Elena’s dressing table have already disappeared from the former diplomat’s mansion in southern Romania. The elderly shepherds and village residents, with whom we still have the chance to talk, are the last representatives of an animal-tending way of life that is close to nature, while at the same time they are witnesses to the history of the former dictatorship, which is sharply delineated even from far away. Coal tubs of closed mines still remain standing, some gigantic frescos promoting the greatness of communism on public buildings can still be seen, and a few faded red stars still appear on dilapidated factory walls.

Our work on this project is based on our own past experience – as children we both, via family ties, regularly crossed over to the neighboring dictatorship of Romania from Hungary’s softening communist world. The winding queues in front of empty food shops and the everyday fear represent a part of our personal memories.

Tamas Dezsö and Eszter Szablyár, September 2015

![]()

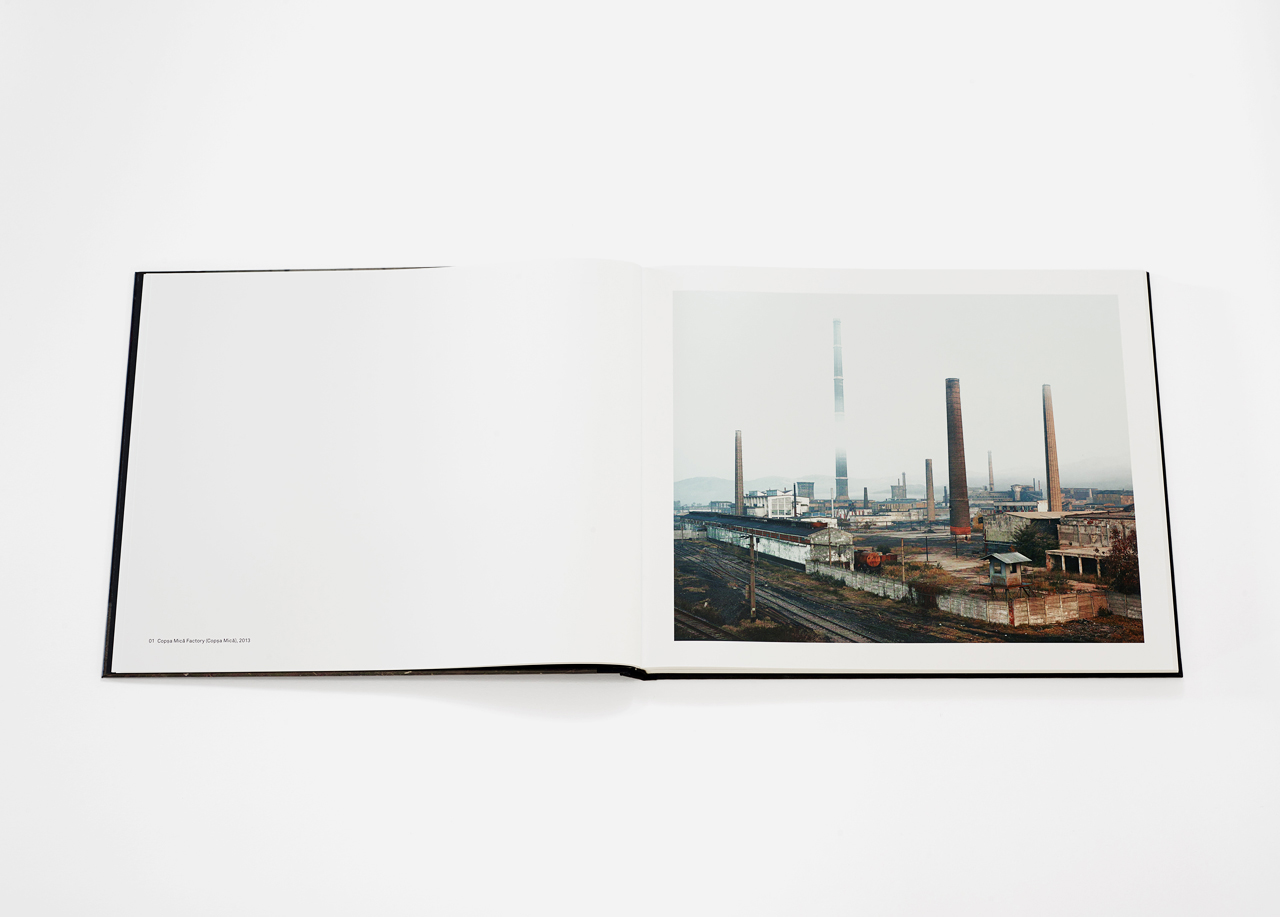

Copșa Mică Factory (Copșa Mică), 2013

It was immediately after the fall of Ceaușescu’s dictatorship when the world learned about Copșa Mică, which became the symbol of the communist system based on enforced industrialization. Journalists arriving in the country were shocked to see what the communist press had kept secret: everything, the houses, people, animals, and the neighboring forests, was covered in black soot. The carbon black plant Carbosin and Sometra, which extracted mainly zinc and lead, opened in the settlement in the 1930s. Following nationalization, during the time of Ceaușescu several thousand workers were moved here, and the capacity of the factories was increased in an absurd manner. As a result, lead emissions exceeded the permitted limit by a thousandfold, and cadmium, carbon dioxide, and sulfur dioxide pollution were several hundred times their allowed maximum. The consequences included lead poisoning, certain congenital disorders, malignant tumors, and increased infant mortality. Animals living in the wild largely disappeared, and even domestic horses did not live longer than a couple of years. Due to contamination, vegetables and fruits grown in the area were permitted to be sold only locally. Factory wages were higher than average, but protesting against the conditions was considered an anti-state crime. Nevertheless, a local doctor sent a detailed report to Ceaușescu. Although the doctor was threatened by the secret police, as a result of his letter, by 1988 a 230-meter-tall chimney had been built that directed poisonous substances farther, alongside shorter chimneys, which retained pollution in the valley. The carbon black plant finally closed in 1993. Since the global crisis of 2009, production has nearly completely stopped at the Sometra factory, which was somewhat modernized before being acquired by a foreign owner. According to experts, the town will be regarded as a dangerous area for decades.

![]() Timofte (Anina), 2013

Timofte (Anina), 2013

The 44-year-old ironworker was born in Moldova and worked there with his wife until their factory closed. Later, after the birth of their child, they moved to Anina, where his wife had grown up. In 2006 the mine, like the other factories, closed in the once-prosperous industrial town, and unemployment remains a severe problem. Timofte and his family live in a dilapidated house in the town center. The three of them, his wife with their ten-month-old baby in her arms, go into the forest behind the mine daily, where they dig out leftover iron for their daily subsistence. Taking metal from the closed-down factories is punishable by prison.

![]() The Flooded Village of Geamăna (Geamăna), 2011

The Flooded Village of Geamăna (Geamăna), 2011

A poisonous deposit covers the former mountain village of Geamăna. A small part of its Greek Catholic church tower can still be seen, though less and less as the years go by. The village was first flooded with water on Ceaușescu’s orders in 1978. It was then gradually filled with poisonous mud arriving as a by-product of the mine that opened in neighboring Roșia Poieni, at the time regarded as the largest copper site in Europe. The state gave the nearly four hundred families living in the village very little time to move before it was flooded, appropriated their houses, and promised to resettle the residents in a newly built place ten kilometers from their original homes. In the end, they received some land a hundred kilometers from Geamăna and a little money, which did not even cover resettlement costs. By now the continually rising mud has covered the whole village with its houses, school, church, and cemetery, including the dead, although the residents had also been promised that the graves would be exhumed. At the time of the revolution, 3,000 people were employed at the open-pit mine, which had a diameter of 800 meters and produced 11,000 metric tons of copper annually. Over the years, roughly 27 million metric tons of material, hazardous because of its pyrite and cyanide content, has reached the subsoil and is causing an environmental catastrophe across an ever larger area. Today hardly a dozen original inhabitants remain in the village, which has no infrastructure. A few have moved uphill as the level of poisonous material rises.

![]() Sheep Farm (Silvașu de Sus), 2012

Sheep Farm (Silvașu de Sus), 2012

In Romania, raising sheep is highly traditional and is based on the grassy land and pastures covering one-third of the country. In mountainous regions unsuitable for mechanized large-scale farming, a significant part of the livestock remained in private hands even under communism, though people were compelled to sell part of their produce to the state. Since work in state farms and cooperatives did not prove efficient, individual farmers continued to ensure the country’s supply. For example, in 1985 they provided half of the annual wool stock. During the decades of communism, sheep were raised mainly for their wool, which was used in light industry, as well as for export to help reduce state debt. The state encouraged farmers to raise livestock with guaranteed high purchase prices. Wool production reached its peak in the mid 1980s. Ceaușescu was fond of using wool carpets to promote Romania’s image. After the political changes, the livestock population of 12 to 16 million dramatically decreased, mainly due to plummeting world market prices and the end of guaranteed rates. Instead of wool, the production of milk, cheese, and meat became primary. Romania regained third place in the EU in terms of its sheep stock, which has recently increased. The sheep in the photograph are part of a flock of between two and three hundred. After summer transhumance they spend the winter at their permanent site. The sheep here have just been driven out of the pen in the dawn frost.

![]() Petru (Vințu de Jos), 2014

Petru (Vințu de Jos), 2014

Petru, a shepherd whose job was passed down from generation to generation, grazes his sheep in the churchyard of Vințu de Jos, which is surrounded by a stone wall. As was usual under communism, the church was used as a furniture warehouse, so it became run down. Petru drives out his own and other villagers’ livestock to the neighboring areas in winter. From spring to autumn, however, he drives them in a semi-nomadic way several hundred kilometers across the mountains. The tradition of so-called transhumance livestock rearing survived even under communism, and in the most destitute times well-to-do shepherds emerged among owners of several thousand animals that remained in private hands. Allegedly, one of them even called Ceaușescu to request permission to buy a helicopter, but the request was refused. Because of the heavy workload, the number of professional shepherds is gradually decreasing today. Shepherds who still wear their traditional costume have a so-called cojoc, a long-sleeved cloak sewn by hand from three or four sheepskins, or a sarică, which can be either sleeveless or have long sleeves. The outside of Petru’s cojoc is covered with fleecy wool. Shepherds who play a mystical role in Romanian cultural history are often popular characters in legends, and they can often be seen on wall paintings in churches and shrines along the roads. Because of their thorough knowledge of the locality, they were often messengers and spies during times of war.

![]() Cheile Lăpușului (Fundul Câmpului), 2014

Cheile Lăpușului (Fundul Câmpului), 2014

In the Lăpuș Gorge area, isolated mountain villages are still clustered. Their inhabitants live in a traditional manner without infrastructure, running water, or electricity. Most make a living from farming and animal husbandry, and logging is also an important source of income. Much of the region, rich in rock formations, waterfalls, and caves, is designated a protected area.

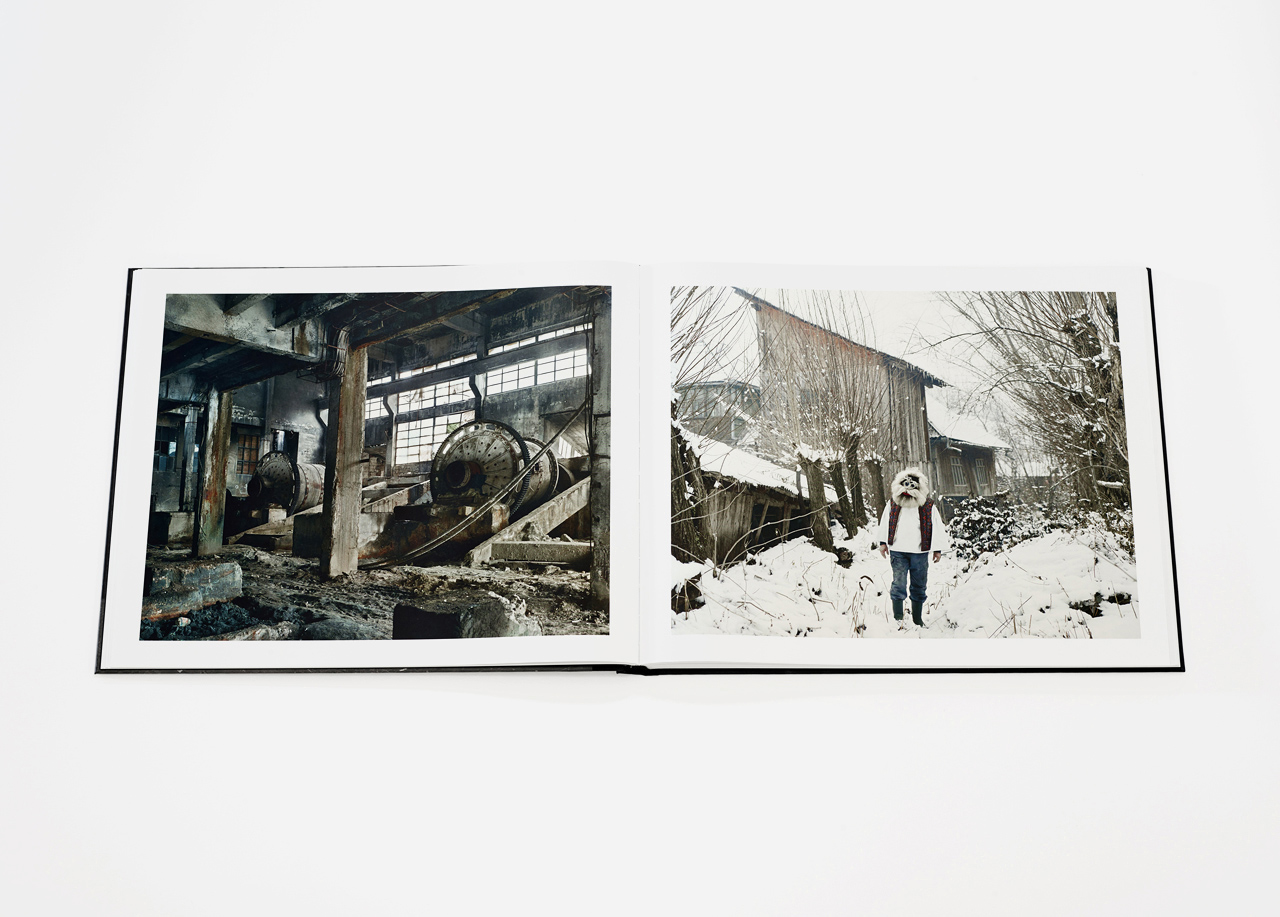

![]() Abandoned Factory (near Hunedoara), 2011

Abandoned Factory (near Hunedoara), 2011

The Hunedoara Steel Works was one of the most significant sites of enforced industrialization and became an obsession of Ceaușescu. Today, production has completely halted, and the plant has been mostly demolished. Construction of the first two iron furnaces began in the gardens of former Franciscan cloisters, and the plant opened in 1884; its products were displayed at the 1900 Paris World’s Fair. Given its long development, it became an early citadel of communist industry. As people were resettled, the town’s population increased rapidly. From about 4,800 in the 1930s, it rose to 36,000 in 1957 and to 90,000 in 1990. The town reached the peak of its development in 1970, when several movie houses, theaters, and stadiums were built. The plant, which operated with increasingly outdated technology, began to decline in the second half of the 1980s. The single-industry town’s workforce of 20,000 had decreased to barely 800 by 2011, due to continuous layoffs and enforced retirement after the political changes. Most young people left the town due to the lack of jobs. The production of crude iron finally stopped in 1999. Alongside the towers of Hunedoara Castle, the eight 90-meter-tall chimneys became a symbol of the town after their construction in 1957, but they have now been demolished. The power plant, built in 1957 and known in local lore as “cursed,” was dismantled over seven years. By now, almost all the buildings have disappeared from the vast industrial area.

![]() Cart Horse (near Silvașu de Sus), 2011

Cart Horse (near Silvașu de Sus), 2011

A cart horse waits for its owner on a frosty winter morning. Since 2008, when horses and carts were banned from main roads for safety reasons, horses now mostly help with plowing. For a long time, oxen were used in agriculture as beasts of burden, but for the past hundred years horses have been employed. During the first three decades of communism, several thousand draft horses were ordered to be slaughtered and replaced by tractors.

![]() Costica (Muntele Mare), 2012

Costica (Muntele Mare), 2012

Costica was born in Bistra, Maramureș County, to a family of farmers. He had ten siblings and finished four years of elementary school. From very early childhood, he took to the mountains, and when he was 16 he began shepherding. From spring to autumn he grazes his own and the villagers’ animals for payment in Muntele Mare. In the mountains the shepherds live in isolation for months. They lack basic infrastructure, draw water from streams, and use kerosene lamps for lighting. Costica spends the rest of the year in the house he inherited from his parents. It is about a five-hour walk from the mountain top down to the village where he and his family farm. Because of the strenuous physical work, getting up at dawn, much walking, and continuously tending the animals, and given his age, he is planning to spend the next summer in the village. As one of the last mountain shepherds in the region, he thinks that this more or less nomadic activity will soon cease to exist, since young people are not continuing the tradition.

![]() Hens and Roosters (near Iara), 2011

Hens and Roosters (near Iara), 2011

Hens and roosters at the edge of the village of Iara are an important part of everyday life. They are kept to supplement the villagers’ meager pensions. In addition, fruit and mushrooms picked in the woods represent some extra foodstuff. Villagers say that during the time of collectivization they regularly had to hand over to the state more eggs than their hens had laid, thus it often occurred that they were compelled to buy the missing numbers from others. There were some who rather killed their hens, given the impossible situation. At the same time, whoever was caught hiding eggs could be sentenced to prison.

![]() Anastasia (Livada), 2012

Anastasia (Livada), 2012

Anastasia Hanc, then 77, moved to Livada from a neighboring village when she married. Her husband’s family farmed a large amount of land and kept buffalo and cattle. Later, under communism, her husband worked at the cement factory in nearby Turda. At home, Anastasia tended the animals, sewed for the villagers, and brought up their two sons, one of whom she delivered in a cart on the way to the hospital. By now the younger people have left the once densely populated village. Her sons moved to town some thirty years ago. As she says, only the elderly and empty houses remain, and there is no one left to fix what breaks. Today they keep only a single piglet and a few hens around the house.

![]() Doftana Prison (Doftana), 2013

Doftana Prison (Doftana), 2013

The 18-year-old Ceaușescu, who was already regarded as a dangerous agitator in 1936, was taken to court for distributing banned leaflets and sentenced to three years in the Doftana prison. The penal institution, 100 kilometers from Bucharest, became the penitentiary for political prisoners, including future communist leader Gheorghiu-Dej and other communists from the 1920s. The inmates distributed their handwritten, internal newspapers The Red Doftana and Jailed Bolsheviksin the prison, notoriously known as the Romanian Bastille. After World War II the prison was turned into a museum with the aim of making propaganda. Later the exhibitions emphasized mostly Ceaușescu’s suffering, and on his personal orders even the pipes that used to conduct hot water were removed from his cell. After his election as president, Ceaușescu himself visited the museum on several occasions. Schoolchildren were taken on obligatory outings to the prison, whichhad turned into a cultic place, and pioneers were ceremonially initiated in its garden. At present, the derelict and dilapidated building cannot be visited.

![]() The Dark Room (Sighetu Marmației), 2012

The Dark Room (Sighetu Marmației), 2012

One of the cruelest locations where anti-communist elements were liquidated was the prison in Sighetu Marmației, a few kilometers from the Ukrainian border. In 1950 several hundred former ministers, government politicians, members of the Academy, religious leaders, and bankers, mostly over 60, were jailed here. The majority lost their lives as a result of the inhumane conditions. In the penal institution, which became known as the Ministers’ Prison because of its high-ranking inmates, prisoners were starved, tortured, and, as the gravest punishment, locked up in the so-called Dark Room. Prisoners, stripped naked, were put in the cold, damp, windowless cell. While locked up they received half their daily food ration and were often handcuffed to the iron ring seen in the middle of the cell. Ice-cold water was sometimes poured on the floor to aggravate their suffering. The prison was closed for good in 1977. The deserted, dilapidated building complex reopened as a museum in 1993, preserving the memory of communism’s victims.

![]() Carpet Sellers (Pojorâta), 2012

Carpet Sellers (Pojorâta), 2012

A Gheorgheni gypsy couple goes from house to house in the mountain villages in the vicinity of Pojorâta to sell carpets made in China and purchased in their hometown. They are planning to return home for Christmas, having been away for half a year. They will live off the money earned from carpet selling until their next trip. There is really no other way for them to gain their livelihood. The traveling way of life for gypsies selling linen, wooden wash tubs, dishes, and carvings they themselves make has been part of their traditional culture for several centuries.

![]() Ciprian, the Bear Dancer (Sălătruc), 2013

Ciprian, the Bear Dancer (Sălătruc), 2013

Seven-year-old Ciprian, dressed in bearskin, is the youngest member of a family that has passed on the tradition of bear dancing from generation to generation for centuries. He received his first skin at the age of one, and since then he has grown out of several sizes. According to the more than one thousand years old tradition with a pagan origin, which has been preserved exclusively in a few villages in the eastern part of Romania, the young and old members of the community don bearskins at Christmas and on New Year’s Day so that, accompanied by drummers and singing women dressed in folk costumes, they would dance around the whole village. According to folk beliefs, the ceremony known in Romanian as Ursul aims to drive away evil spirits and keep them at bay. It takes a long time to make the costume, the tongue is made of wood, glass or plastic is used for the eyes, and a ring is attached to the nose. For the time of the dance a long chain is fixed to the ring, and the bear’s ears are decorated with red tassels. A well-fashioned skin can last decades, though it needs looking after with great care. The rarely worn skins are sprinkled with tobacco to protect them from moths, and after wear they are thoroughly dried out, then rubbed with oil. The highly valuable costumes, which can even weigh 70 kilos, represent great prestige for their owners. Ciprian’s father, who is a custodian of the tradition in Sălătruc, has 14 bearskins, since villagers who have moved abroad left several skins in his care.

![]() Ileana (Fața Roșie, Bătrâna), 2014

Ileana (Fața Roșie, Bătrâna), 2014

Ileana Toma, 83, was born in the small village of Răchițaua, Hunedoara County. Her father was regarded as a wealthy man, the family had large estates, they ground flour in their own mill, and their vast number of animals, mainly buffalo, were also looked after by Ileana from a very young age. Not all of her six siblings could attend school, and that was also true for Ileana. With nationalization they were deprived of all they had. Later, in 1958, Ileana married and moved to her husband’s neighboring mountain village of Fața Roșie. She has lived there ever since. They still harvested by hand in the village, which traditionally lived on farming and animal husbandry, and everyone made horseshoes and tools at home. Living conditions have not changed much for a century: there is no connection to the electricity grid or running water, so lighting is provided with the help of a generator, and Ileana, who has lived on her own for many years, carries water in a five-liter can from a well a fair distance away. Mail is delivered once a month and bread is brought by a mobile shop twice a week to the aging village, which has seven remaining families. Today Ileana keeps only a few chickens and roosters. She collects and dries herbs she finds nearby and puts away apples she picks in the summer for winter.

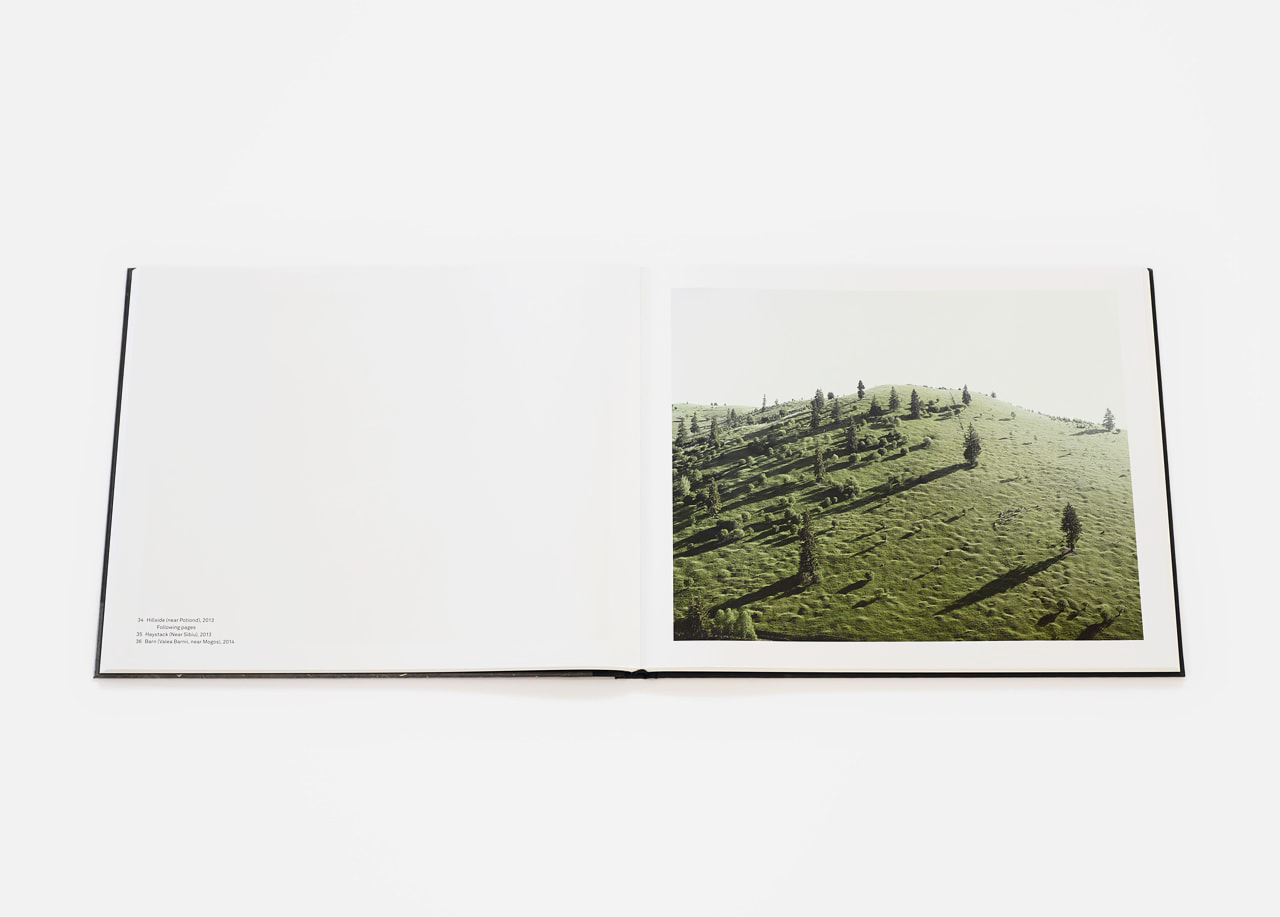

![]() Hillside (near Potiond), 2013

Hillside (near Potiond), 2013

The population of Harghita County in the Eastern Carpathians is traditionally involved in animal husbandry and land cultivation. Tree felling and salt mining also represent an important source of income. The photograph shows an alpine pasture at the Ghimeș Pass at dawn. Harghita County named after the mountain was established by Ceaușescu’s administrative reform in 1968.

![]() Chair (Ursici), 2013

Chair (Ursici), 2013

Every object of use is carefully kept in the isolated mountain villages. The elderly couple who live off shepherding and farming the land are repainting a room and the chair is placed there to rest on. It has already undergone several repairs. The blue paint, which is considered to ‘enclose’ the space, used to be home-made from natural materials.

![]() Sitting Bear (near Zărnești), 2013

Sitting Bear (near Zărnești), 2013

Bears were held under cruel conditions in many places across the country, both before and even after the revolution. Bears kept in circuses or as pets in confined cages, used for bear-dancing, or tied in front of restaurants, were mostly severely underfed. To rescue these animals, a special safety shelter, the Libearty Bear Sanctuary, was founded in the mountains near Zărnești in 2005. These days, more than seventy bears live in the 70 hectares of oak forest. The bear in the photograph arrived with its sibling in 2006. The then two-year-old cubs were in such bad condition that it took nearly five years for them to completely recover. Although before, or even after, the revolution, bears were not regarded as animals of some value requiring special protection, Ceaușescu banned the general hunting of bears, keeping the privilege for himself alone.

![]() Sodium Factory (Ocna Mureș), 2012

Sodium Factory (Ocna Mureș), 2012

In 1896 the Solvay Sodium and Ammonia Factory was established with Belgian and German capital in Ocna Mureș, which was famous for its vast salt mines. It produced several thousand tonnes of soda annually. Given the expanding labor force, in 1955 the factory was joined by its own workers’ housing estate. Due to the production methods, which became increasingly out-dated, the by-product dumped in the river Mureș caused severe pollution and in the 1960s intoxicated fish were caught by the basketful. The factory was sold in 2001 and in 2010 it finally closed because of accumulated debts and was partly demolished. Since it was one of the largest production units in the region, the lay-offs resulted in severe unemployment.

![]() Choir (near Abrud), 2012

Choir (near Abrud), 2012

The Moti people with their own dialect and customs living in isolated tiny villages in the Apuseni Mountains form an independent ethnographic group. Their ancestors were granted various benefits to encourage them to settle in the forbidding mountainous region, which could only offer a hard life. They were mainly involved in mining, animal husbandry, shepherding, tree felling, gold-washing and making fur coats. They adapted their architecture to the conditions, such that their houses and farms, which are scattered across the mountains, are fixed to the sides of the mountains and supported with beams. The photograph shows a choir in folk costume going to the church for a local festival. More or less every small village has its own choir, which still represents a significant part of communal life.

![]() Huts (near Moisei), 2011

Huts (near Moisei), 2011

The mountainside that is situated by Maramureş County’s most ancient village, Moisei, records of which date from the 1200s, is a traditional area of shepherding and related activities. The Ruthenians living there have been fond of using the rickstands, that look like a long-stretching fence and are less common in other regions. The huts are for storing hay and are characteristic of the Carpathian Basin. They have a single space and are built from planks or slats in meadows far from the village. They have solid roofs and lockable doors.

![]() Victor (near Geamăna), 2011

Victor (near Geamăna), 2011

Victor Purda, 85, was born as one of 12 children in a family that worked on the land and raised livestock in Geamăna. Today his family’s house, the school he attended and the graves of his parents buried in the churchyard are covered with the poisonous mud conducted from the nearby copper mine, which flooded the village on Ceauşescu’s orders from 1978. Victor, who was employed as a day-laborer and then worked in the copper mine for decades, married at the young age of 22. He and his wife brought up eight children who have all left the village seeking better employment opportunities in the nearby towns. Now on his own, Victor uses a kerosene lamp for lighting and draws water from a nearby well, since his house has no connected electricity and no running water. To supplement his pension he keeps a few cows and hens, and himself makes cottage and other types of cheese. Once a week he goes by horse and cart to the nearest town, Turda, to buy bread.

![]() Tunnel (near Vidraru Dam), 2013

Tunnel (near Vidraru Dam), 2013

The construction of a hydroelectric power plant with the Vidraru dam, which was intended to be a symbol of industrialization, began under Gheorghiu-Dej in 1961, but it was his successor, Ceaușescu, who opened it in 1965. 1.7 million cubic meters of rock and earth were moved, 930,000 cubic meters of concrete were used and tunnels totaling 42 kilometers in length were dug and blasted, including the one in the picture. During construction, which involved cutting-edge technology, ten thousand workers labored 10-12 hours a day. Twenty of them died. Today only a few cars and carts pass daily through the tunnel, which has no lighting and is protected against the danger of landslips by a rusting net. The tunnel leads to Lake Vidraru, which was artificially created by flooding a relocated village. The Securitate, Romania’s secret police, had its own office on the site. The construction, which on its opening was regarded as the world’s ninth largest power station, is situated a couple of hundred meters above the castle of Vlad Țepeș, the legendary Count Dracula.

![]() Lupeni Coal Mine (Lupeni, Jiu Valley), 2014

Lupeni Coal Mine (Lupeni, Jiu Valley), 2014

The most significant political demonstration against the system before the revolution took place in the town of Lupeni, the site of Romania’s largest coal mine. In the mono-industrial region of the Jiu Valley, with its one and a half centuries of coal mining tradition, the miners reacted to the increasingly worsening living condition with a strike in summer 1977. The 35,000 miners who gathered in Lupeni were willing to negotiate, but only with Ceaușescu. Interrupting his holiday by the sea, Ceaușescu appeared on the site guarded by the army and the secret police. In his speech, which he delivered trembling, he promised everything. However, having failed to keep his promises, there followed a wave of reprisals lasting several months. The demonstrators were summoned to the offices of the Securitate, and several thousand people were resettled and sent to prison and labor camps. After the revolution production fell and later mine closures accelerated. The mine in Lupeni is still operating, although most of the units in the coal preparation plant seen in the photograph have not been modernized since Ceaușescu’s time. Due to high unemployment, many of the workers who were moved here have returned to their native villages and the young continue to leave the town.

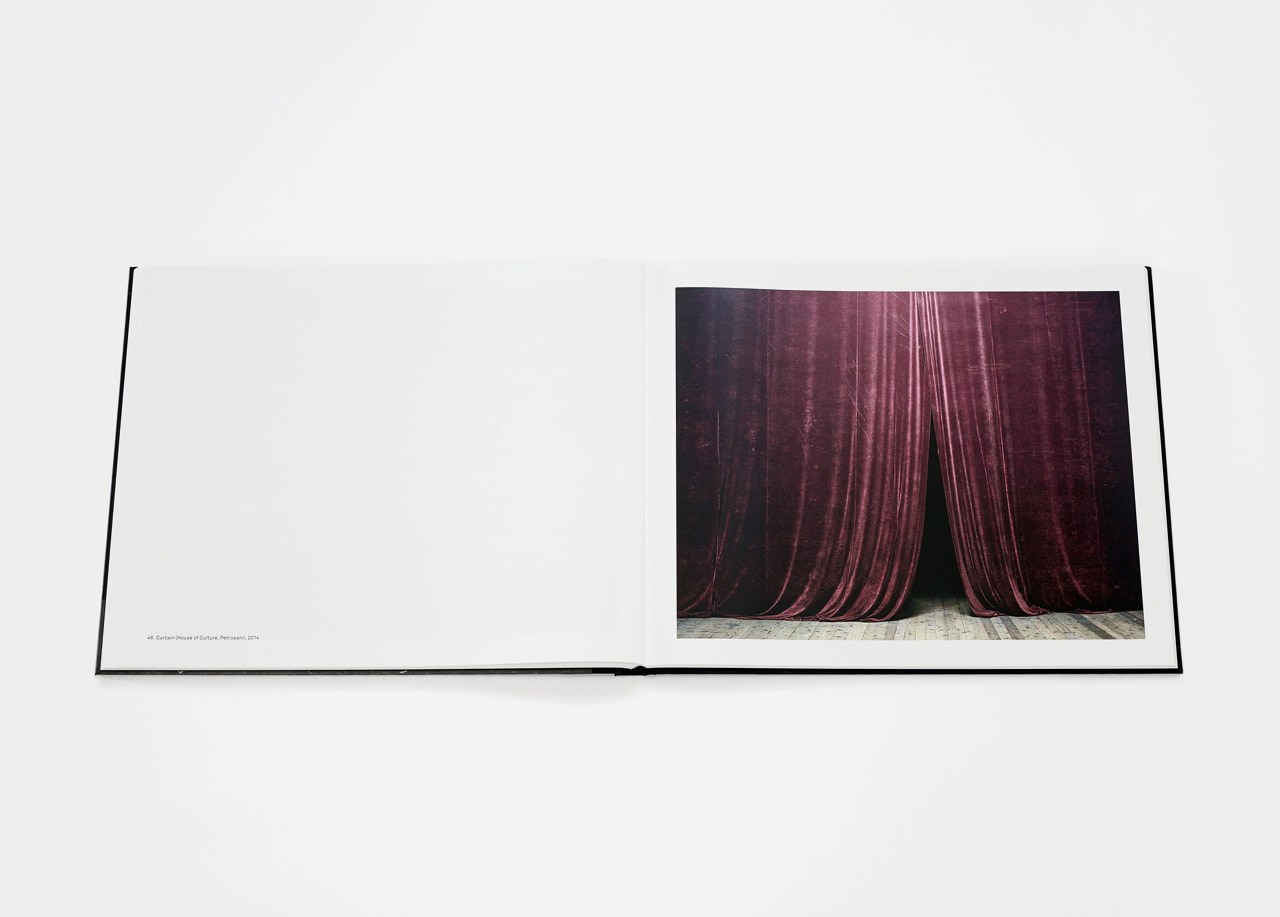

![]() Curtain (House of Culture, Petroșani), 2014

Curtain (House of Culture, Petroșani), 2014

The House of Culture seating 600 people was built on the main square of Petroșani, a mining town in the Jiu Valley, in 1966. It staged concerts, opera and theatre performances. Local party meetings were also organized there. However, Ceaușescu never appeared, since a public of 600 people did not prove an imposing enough audience for him. Instead, he chose to deliver a speech in the nearby stadium. Although very rarely, performances are still held in the ceremonial hall of the run-down building. The hall’s velvet curtain dates from 1966.

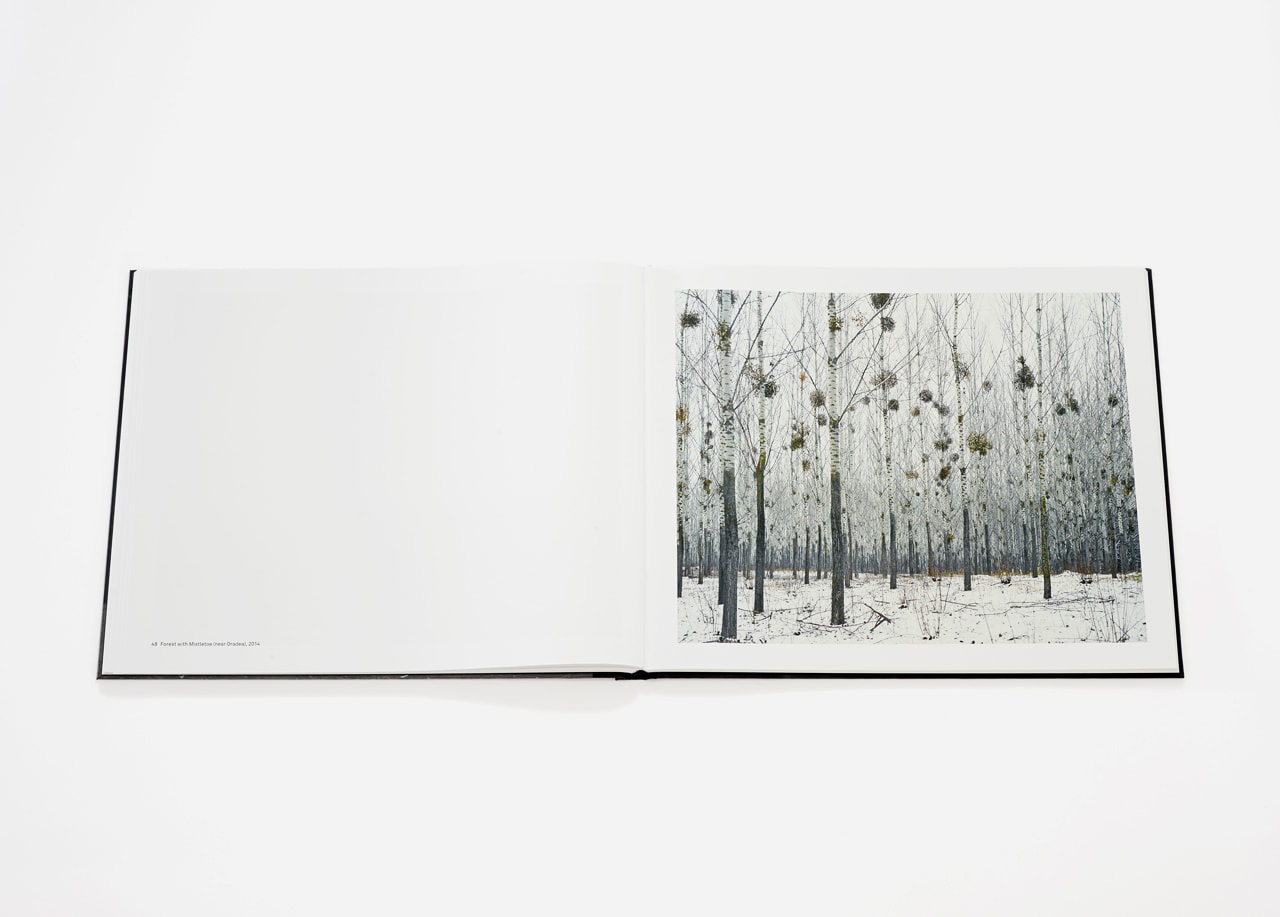

![]() Forest with Mistletoe (near Oradea), 2014

Forest with Mistletoe (near Oradea), 2014

Today Romania has 6.5 million hectares of forests. Several statutes were adopted in connection with the protection of forests during the dictatorship. For example, in 1947 the forest as national wealth was stipulated and the preservation, protection and development of forests, as well as rational logging, were decreed by law in 1987. Large-scale, illegal logging has presented a grave problem since the revolution.

![]() Dump (near Aiud), 2012

Dump (near Aiud), 2012

Romania’s grave legacies include soil, air and water pollution caused by plants using out-of-date technologies, as well as dumps. Nearly all the country’s communal rubbish is taken to tips. To this day dumps, some of which are extremely high, often contain poisonous materials as well as carcasses and can be found just outside towns such as Aiud. Due to unemployment as a result of factory closures and the impoverishment of certain social strata, whole families move into dumps by shaping tunnels hollowed in the rubbish and living in holes that protect them against the cold.

![]() Shepherd (near Mediaș), 2013

Shepherd (near Mediaș), 2013

In the traditional peasant world a horse was a constant companion. As elderly people often remark: “There was nothing else but man and horse.” People moved around with the help of horses, they sowed and ploughed with horses, and the priest and doctor reached isolated villages on horseback. Although a huge number of horses fell victim to the industrializing zeitgeist of the dictatorship, horses still play an important role in country life. The shepherd in the photograph is riding early morning to the plateau through the forest near Mediaș in Sibiu County to feed and give water to the flock, which is kept in distant pens even in winter.

![]() Maria (Dealul Corbului), 2014

Maria (Dealul Corbului), 2014

Maria Horean, 77, lives in a 130-year-old house in Dealul Corbului, an isolated mountain village of hardly fifty residents in Maramureș County. Like so many in the region, her livelihood is based on cultivating the land and animal husbandry. She grows wheat and corn, and rears cows and pigs. She makes jam from the fruits of apple, pear and old plum trees, and she distills fruit brandy, tuica as is called locally, and bakes her own bread. Maria has also made most of her clothes from hemp and wool. The huge quantity of snow that often comes down all at once in winter still cuts off the village for weeks.

![]() Scrap Metal Collector (near Hunedoara), 2011

Scrap Metal Collector (near Hunedoara), 2011

The Hunedoara Steel Works was regarded as one of the most significant bases of enforced industrialization. Following its nearly complete standstill, the majority of the former factory buildings have been demolished and the remains are taken away by illegal scrap collectors. The man in the photograph used to work in the factory, as did his wife. Since their dismissal they have been trying to live off the sale of collected iron, like hundreds of others in the town, which is struggling with severe unemployment.

![]() Trees (near Suceava), 2012

Trees (near Suceava), 2012

The frozen traces of logging in the outskirts of the small north-eastern Romanian mountain village can be seen for quite a long time in the snow. Woodcutters push the logs down earth channels especially shaped on the sloping hillside. Then they still transport the wood by horse-drawn carts to distant, large timber yards.

![]() Nechifor (Ursici), 2013

Nechifor (Ursici), 2013

At the age of seven, Nechifor Toncea, now 90, began crossing the mountains with his father and a flock of several hundred sheep to learn shepherding. His parents did not allow him to attend school in order for him to stay with the livestock, but later he learnt to read and write when he was in the army. Nechifor, who married and moved to Ursici, a mountain village in Hunedoara County, would be away with the flock for months every year. During that time his wife ran the household and brought up their two children. Nechifor and his wife still make their living from rearing cows and pigs, and their mountain holding has a vegetable garden, an orchard and meadows. They may not meet neighbors who have settled scattered on the nearby mountainsides for years.

![]() Cooling Towers (near Călan), 2011

Cooling Towers (near Călan), 2011

The steel plant of Călan that opened in the 1870s and was later extended became Romania’s number one cast iron producer during communism. In its golden age the factory employed 8,000 workers. Of those, only seventy remained employed by 2010, due to the rapid decline, privatization and lay-offs after the revolution. Owing to unemployment in the town, scrap metal collectors occupied the site of the mostly closed down factory and caused the majority of the buildings, including the two cooling towers, to deteriorate.

![]()

Notes for an Epilogue, Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco, 2016

![]()

Notes for an Epilogue, Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco, 2016

![]()

Notes for an Epilogue, Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco, 2016

Notes for an Epilogue, Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco, 2013, image by Balazs Gardi

Notes for an Epilogue, Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco, 2013, image by Balazs Gardi

Notes for an Epilogue, Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco, 2013, image by Balazs Gardi

![]()

Notes for an Epilogue, Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco, 2013, image by Balazs Gardi

![]()

Notes for an Epilogue, Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco, 2016

![]() Timofte (Anina), 2013

Timofte (Anina), 2013![]() The Flooded Village of Geamăna (Geamăna), 2011

The Flooded Village of Geamăna (Geamăna), 2011![]() Sheep Farm (Silvașu de Sus), 2012

Sheep Farm (Silvașu de Sus), 2012![]() Petru (Vințu de Jos), 2014

Petru (Vințu de Jos), 2014![]() Cheile Lăpușului (Fundul Câmpului), 2014

Cheile Lăpușului (Fundul Câmpului), 2014![]() Abandoned Factory (near Hunedoara), 2011

Abandoned Factory (near Hunedoara), 2011![]() Cart Horse (near Silvașu de Sus), 2011

Cart Horse (near Silvașu de Sus), 2011![]() Costica (Muntele Mare), 2012

Costica (Muntele Mare), 2012![]() Hens and Roosters (near Iara), 2011

Hens and Roosters (near Iara), 2011![]() Anastasia (Livada), 2012

Anastasia (Livada), 2012![]() Doftana Prison (Doftana), 2013

Doftana Prison (Doftana), 2013![]() The Dark Room (Sighetu Marmației), 2012

The Dark Room (Sighetu Marmației), 2012![]() Carpet Sellers (Pojorâta), 2012

Carpet Sellers (Pojorâta), 2012![]() Ciprian, the Bear Dancer (Sălătruc), 2013

Ciprian, the Bear Dancer (Sălătruc), 2013![]() Ileana (Fața Roșie, Bătrâna), 2014

Ileana (Fața Roșie, Bătrâna), 2014![]() Hillside (near Potiond), 2013

Hillside (near Potiond), 2013![]() Chair (Ursici), 2013

Chair (Ursici), 2013![]() Sitting Bear (near Zărnești), 2013

Sitting Bear (near Zărnești), 2013![]() Sodium Factory (Ocna Mureș), 2012

Sodium Factory (Ocna Mureș), 2012 ![]() Choir (near Abrud), 2012

Choir (near Abrud), 2012![]() Huts (near Moisei), 2011

Huts (near Moisei), 2011![]() Victor (near Geamăna), 2011

Victor (near Geamăna), 2011![]() Tunnel (near Vidraru Dam), 2013

Tunnel (near Vidraru Dam), 2013![]() Lupeni Coal Mine (Lupeni, Jiu Valley), 2014

Lupeni Coal Mine (Lupeni, Jiu Valley), 2014![]() Curtain (House of Culture, Petroșani), 2014

Curtain (House of Culture, Petroșani), 2014![]() Forest with Mistletoe (near Oradea), 2014

Forest with Mistletoe (near Oradea), 2014 ![]() Dump (near Aiud), 2012

Dump (near Aiud), 2012![]() Shepherd (near Mediaș), 2013

Shepherd (near Mediaș), 2013![]() Maria (Dealul Corbului), 2014

Maria (Dealul Corbului), 2014![]() Scrap Metal Collector (near Hunedoara), 2011

Scrap Metal Collector (near Hunedoara), 2011![]() Trees (near Suceava), 2012

Trees (near Suceava), 2012![]() Nechifor (Ursici), 2013

Nechifor (Ursici), 2013![]() Cooling Towers (near Călan), 2011

Cooling Towers (near Călan), 2011

Timofte (Anina), 2013

Timofte (Anina), 2013 The Flooded Village of Geamăna (Geamăna), 2011

The Flooded Village of Geamăna (Geamăna), 2011 Sheep Farm (Silvașu de Sus), 2012

Sheep Farm (Silvașu de Sus), 2012 Petru (Vințu de Jos), 2014

Petru (Vințu de Jos), 2014 Cheile Lăpușului (Fundul Câmpului), 2014

Cheile Lăpușului (Fundul Câmpului), 2014 Abandoned Factory (near Hunedoara), 2011

Abandoned Factory (near Hunedoara), 2011 Cart Horse (near Silvașu de Sus), 2011

Cart Horse (near Silvașu de Sus), 2011 Costica (Muntele Mare), 2012

Costica (Muntele Mare), 2012 Hens and Roosters (near Iara), 2011

Hens and Roosters (near Iara), 2011 Anastasia (Livada), 2012

Anastasia (Livada), 2012 Doftana Prison (Doftana), 2013

Doftana Prison (Doftana), 2013 The Dark Room (Sighetu Marmației), 2012

The Dark Room (Sighetu Marmației), 2012 Carpet Sellers (Pojorâta), 2012

Carpet Sellers (Pojorâta), 2012 Ciprian, the Bear Dancer (Sălătruc), 2013

Ciprian, the Bear Dancer (Sălătruc), 2013 Ileana (Fața Roșie, Bătrâna), 2014

Ileana (Fața Roșie, Bătrâna), 2014 Hillside (near Potiond), 2013

Hillside (near Potiond), 2013 Chair (Ursici), 2013

Chair (Ursici), 2013 Sitting Bear (near Zărnești), 2013

Sitting Bear (near Zărnești), 2013 Sodium Factory (Ocna Mureș), 2012

Sodium Factory (Ocna Mureș), 2012  Choir (near Abrud), 2012

Choir (near Abrud), 2012 Huts (near Moisei), 2011

Huts (near Moisei), 2011 Victor (near Geamăna), 2011

Victor (near Geamăna), 2011 Tunnel (near Vidraru Dam), 2013

Tunnel (near Vidraru Dam), 2013 Lupeni Coal Mine (Lupeni, Jiu Valley), 2014

Lupeni Coal Mine (Lupeni, Jiu Valley), 2014 Curtain (House of Culture, Petroșani), 2014

Curtain (House of Culture, Petroșani), 2014 Forest with Mistletoe (near Oradea), 2014

Forest with Mistletoe (near Oradea), 2014  Dump (near Aiud), 2012

Dump (near Aiud), 2012 Shepherd (near Mediaș), 2013

Shepherd (near Mediaș), 2013 Maria (Dealul Corbului), 2014

Maria (Dealul Corbului), 2014 Scrap Metal Collector (near Hunedoara), 2011

Scrap Metal Collector (near Hunedoara), 2011 Trees (near Suceava), 2012

Trees (near Suceava), 2012 Nechifor (Ursici), 2013

Nechifor (Ursici), 2013 Cooling Towers (near Călan), 2011

Cooling Towers (near Călan), 2011