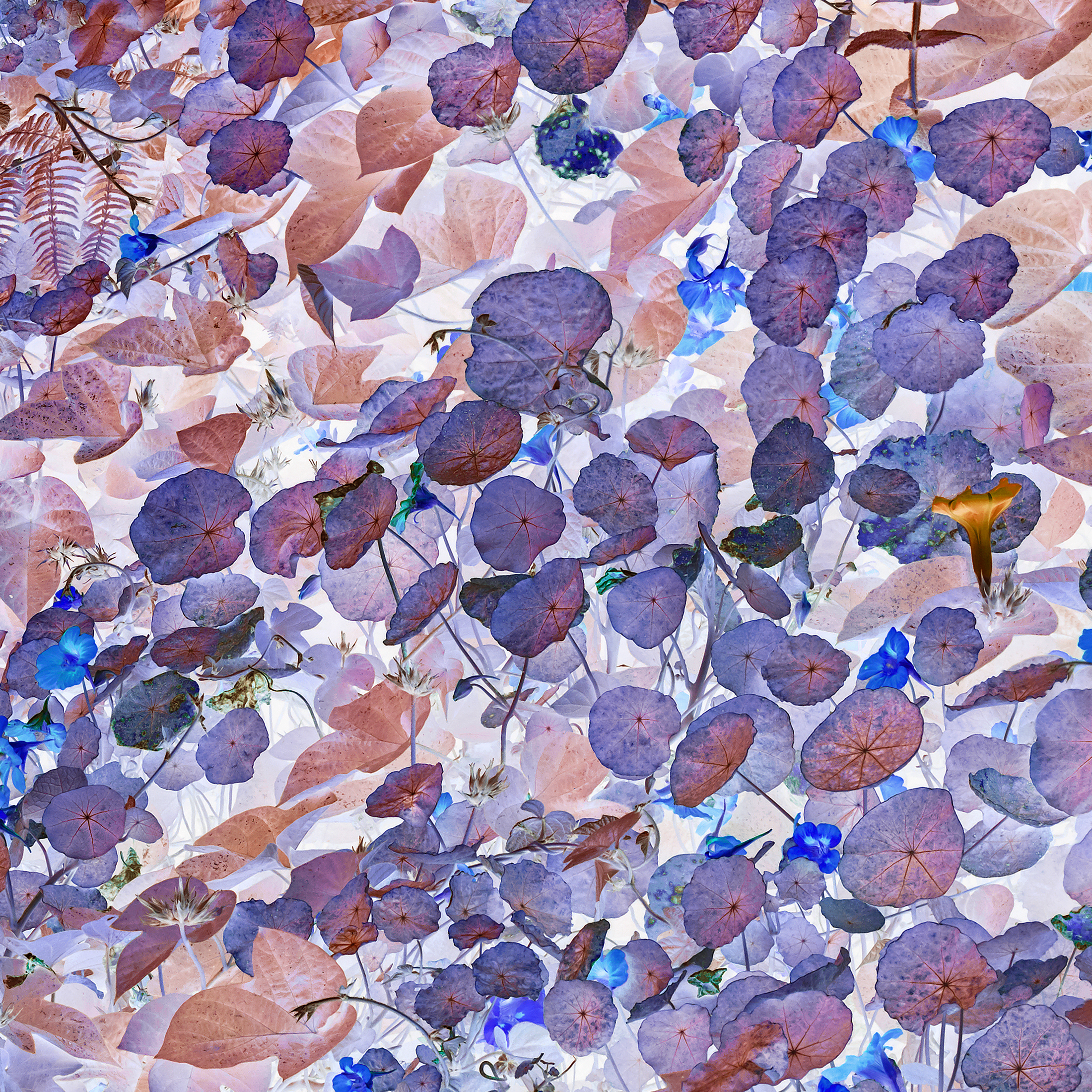

installation view: Tamas Dezsö, Hypothesis: Everything is Leaf, Robert Capa Contemporary, Budapest, Hungary, 2022

“It never occurs to people that the one who finishes something is never the one who started it, even if both have the same name, for the name is the only thing that remains constant.” José Saramago, The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis, 1984

Garden of Persistence, 2020-2022, kinetic table, wood, steel wire, magnets, antique metronomes, 19th century herbarium specimens, 110 x 200 x 120 cm

Tamas Dezsö

Hypothesis: Everything is Leaf

Capa Center

In his latest work Tamas Dezsö investigates the personal identity of all living creatures, including humans. What is the mysterious and inexplicable link that connects personalities of all living entities throughout life? We are in constant change physically: similarly to other living beings, almost all molecules of a human body turn into new ones continuously. We are also in constant transformation intellectually: our way of thinking changes throughout our whole life. So what, then, is identity? How can we identify ourselves as the very same person all along despite these changes? Looking at ourselves at the ages of ten and fifty there is more difference than similarity. A seed and a tree with widely spreading branches grown from the seed do not apparently hold anything in common, yet we are talking about the same living organism.

Hypothesis: Everything is Leaf

Capa Center

Budapest, Hungary

September 22 – February 28, 2023

Atelier Augarten

Atelier Augarten, Vienna, Austria

March 9, 2022 – March 27, 2022

UGM Studio

Maribor, Slovenia

August 27 – October 9, 2022

In his latest work Tamas Dezsö investigates the personal identity of all living creatures, including humans. What is the mysterious and inexplicable link that connects personalities of all living entities throughout life? We are in constant change physically: similarly to other living beings, almost all molecules of a human body turn into new ones continuously. We are also in constant transformation intellectually: our way of thinking changes throughout our whole life. So what, then, is identity? How can we identify ourselves as the very same person all along despite these changes? Looking at ourselves at the ages of ten and fifty there is more difference than similarity. A seed and a tree with widely spreading branches grown from the seed do not apparently hold anything in common, yet we are talking about the same living organism.

Studying the issues of identity, Tamas Dezsö finds the metaphor of human existence in plants, which are built up from the same material and similar structures as ourselves. Every living being – whether human or non-human – is constituted by the same material, which is almost the same age as the universe. In other words, everything that is living represents a transitionary stage of an immense metamorphosis. The elements making up our bodies have already been parts of other bodies at a different place and time, and they are in us only temporarily: we are mediatory media of alien materials. So a separate environment does not exist, there are only various existing, living creatures in infinite forms.

A forest is constantly changing and undergoing millions of transformations – the leaves change, trees that make up the forest only live up to a few hundred years. However, despite that, even over millions of years, we speak about the same forest, provided it remains in the same location. How can we speak about the same forest when all its molecules have been replaced many times over the centuries?

Works by Tamas Dezsö represent a heterogeneous assembly, a kind of Wunderkammer. Initially they are presented from a great distance and reach microscopic proximity: from a far off view of a forest taking shape from millions of leaves in graphic detail to the tiniest part of the surface of an enlarged leaf. The species of a plant can be identified even by its microscopic part, yet no two identical entities exist, even if they are of the same species.

The title of the work quotes Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who zealously researched the identity of plants and during his journeys he wrote in his diary: "Hypothesis: everything is leaf, and through this simplicity the greatest diversity becomes possible." Tamas Dezsö’s work is a collection of thought experiments whereby during the interpretation of the issues of identity, the question is emphatically raised whether it is possible to retune the anthropocentric approach which has marginalised vegetal existence for thousands of years. Why does the many-million-year-old vegetal existence constantly surrounding us seem so unknown and alien to us? While the complete elimination of arbitrary, anthropocentric classification has become of vital importance, is it possible to understand the radical difference of plants when it still appears hopeless to accept difference between human beings?

In relation to the ecological crisis it has become imperative that we handle plants in accordance with their significance, and alongside the troubling feeling of the constantly deepening delay, make serious efforts in order to understand not only human identity, but also the issues of fragile vegetal existence – and not merely because our own existence depends and relies on it.

István Virágvölgyi

curator

inderwelt, 2021-2022, convex oval mirror made from a piece of the Campo del Cielo meteorite,

archival pigment prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, photographs taken of 19th

century fairyfly (Mymaridae) microscope slides, triptych, 130 x 320 x 6 cm

“The introduction to the exhibition, the inderwelt (2021-2022) triptych – a slap in the face of daddy Heidegger – already shows how the entire exhibition operates. We encounter three large-scale photographs with the same background and with the image of an insect on the right and a different one on the left, while there is a mirror-like oval something in the central photograph. From the inscription on the wall we learn that we are looking at something that we could not basically see and we would not see it as we do now. A fairyfly, one of the smallest insects in the world, is imperceptible to the naked eye, while the small mirror-like object is a highly polished piece of a 4.5-billion-year-old meteorite which hit the Earth several thousand years ago. The background in the photos, which is reminiscent of a starry sky, is purely dust, since the photograph of a microscope’s glass plate is reversed into negative making the stains of dirt visible in this enlargement and this size.” Text by György Cséka, Hypothesis: Everything is Leaf exhibition review, A mű, 2022

inderwelt, 2021-2022, convex oval mirror made from a piece of the Campo del Cielo meteorite, archival pigment prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper,

photographs taken of 19th century fairyfly (Mymaridae) microscope slides, triptych, 130 x 320 x 6 cm

inderwelt, 2021-2022, convex oval mirror made from a piece of the Campo del Cielo meteorite, archival pigment prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper,

photographs taken of 19th century fairyfly (Mymaridae) microscope slides, triptych, 130 x 320 x 6 cm, installation view: Robert Capa Contemporary, Budapest, Hungary, 2022

“An oak, that grows from a small plant to a large tree, is still the same oak; though there be not one particle of matter, or figure of its parts the same. An infant becomes a man.” David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature, 1739

Forest, 2018, archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, diptych, 155 x 250 cm

Forest, 2018, detail, archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, diptych, 155 x 250 cm

Forest, 2018, detail, archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, diptych, 155 x 250 cm

Forest, 2018, archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, diptych, 155 x 250 cm, installation view: Robert Capa Contemporary, Budapest, Hungary, 2022

“This is not our world with trees in it. It’s a world of trees, where humans have just arrived.” Richard Powers, The Overstory, 2018

Totem Conflatura, 2022, western red cedar, aluminium, 240 x 85 x 25 cm

Totem Conflatura was directly inspired by the large-scale forest fires devastating the woods in the Sierra Nevada. In the Sequoia National Park local firefighters wrapped fire-proof aluminium covers around the feet of the huge several-thousand-year-old trees. Aluminium covers can cope with intensive heat only for a very short time, since the melting point of aluminium is 660°C or 1220°F, which is far lower than the inner temperature (1100°C or 2000°F) of forest fires in recent years. The history of melting and shaping various metals goes back to the early period of the Anthropocene and it fundamentally changed the relationship between man and nature. Aluminium production is one of the most energy intensive and polluting manufacturing processes on the planet.

Totem Conflatura, 2022, detail

Totem Conflatura, 2022, detail

“Firm, immobile, and exposed to the elements to the point of merging with them. Suspended in the air, effortlessly, without having to contract a single muscle. A bird without flight. The leaf is the first great reaction to the conquest of terra firma, the principal result of the terrestrialization of plants, the expression of their passion for aerial life. It is on leaves that rests not only the life of the individual to which they belong, but also the life of the kingdom of which they are the most typical expression, that is, the whole biosphere. To grasp the mystery of plants means to understand leaves - from all points of view, and not just from the isolated perspectives of genetics and evolution. In them is unveiled the secret of what we call the climate.” Emanuele Coccia, The Life of Plants: A Metaphysics of Mixture, 2018

Garden (afterimage), 2017-2022, archival pigment prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, diptych, 155 x 250 cm

Garden (afterimage), 2017-2022, detail, archival pigment prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper

Garden (afterimage), 2017-2022, detail, archival pigment prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper

“The soil is a medium in which various actors manifest themselves, then disappear. It is a peculiar scene of appearances and retreats, which are pervaded by various rhizomatic roots and vegetal modes of existence. Within this medium rhizomatic arrangements are functioning, making even the apparently deserted areas liveable. When Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari wrote about the collective arrangements of enunciation, they thought of the unaware acquirement and transfer of ecological information in the rhizomatic operation. Each plant needs to entirely fill its environment, while it lives unreflected among its own networks and elements. Vegetal existence is also an elementary existence, living together with compounds, climate change and particles.” Márk Horváth, Hypothesis: Everything is Leaf exhibition review, Orszagút, 2022

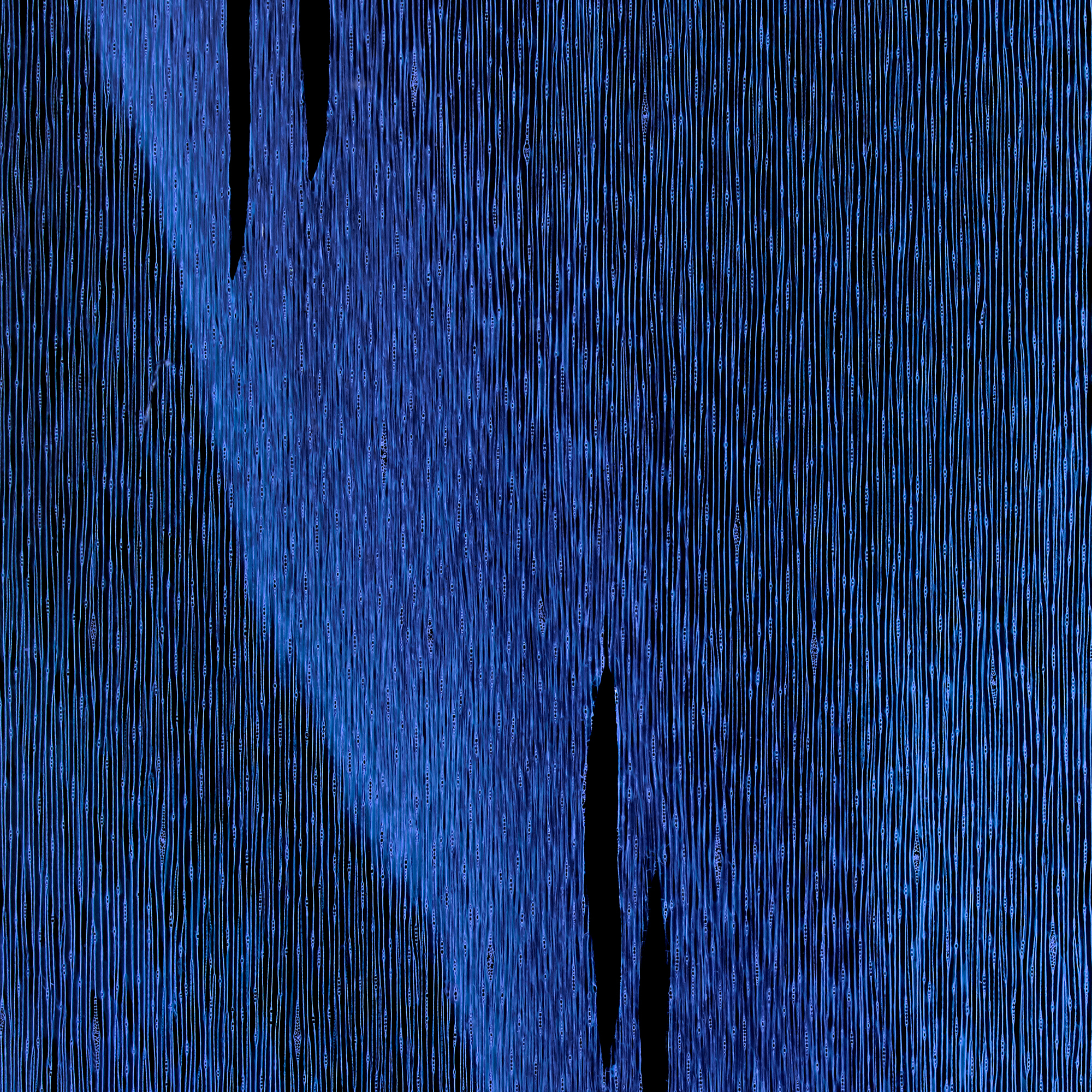

Equisetum, 2019, archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, diptych, 127 x 210 cm

![]()

Equisetum, 2019, detail, archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, diptych, 127 x 210 cm

The origin of the word Equisetum comes from two Latin words: equus (horse) and saeta (bristle or hair). The forerunners of Equisetum (Horsetail) developed in the early Devonian period 400 million years ago. In the following millions of years they dominated the undergrowth, yet some subspecies grew as high as 30 metres, accounting for forests of huge areas. Equisetum is a “living fossil” reminding us of an era when plants did not yet have the ability to flower, relying exclusively on minerals, water and light. Living fossils occupy a special, mystical place in the science of evolution theory because, on the one hand, they survived all the extinction events and, on the other, in their case for some reason further development presumed by evolutionary theories did not lead to new forms. Thus Equisetum itself causes confusion in the scientific concept of time, in scientific thinking.

The origin of the word Equisetum comes from two Latin words: equus (horse) and saeta (bristle or hair). The forerunners of Equisetum (Horsetail) developed in the early Devonian period 400 million years ago. In the following millions of years they dominated the undergrowth, yet some subspecies grew as high as 30 metres, accounting for forests of huge areas. Equisetum is a “living fossil” reminding us of an era when plants did not yet have the ability to flower, relying exclusively on minerals, water and light. Living fossils occupy a special, mystical place in the science of evolution theory because, on the one hand, they survived all the extinction events and, on the other, in their case for some reason further development presumed by evolutionary theories did not lead to new forms. Thus Equisetum itself causes confusion in the scientific concept of time, in scientific thinking.

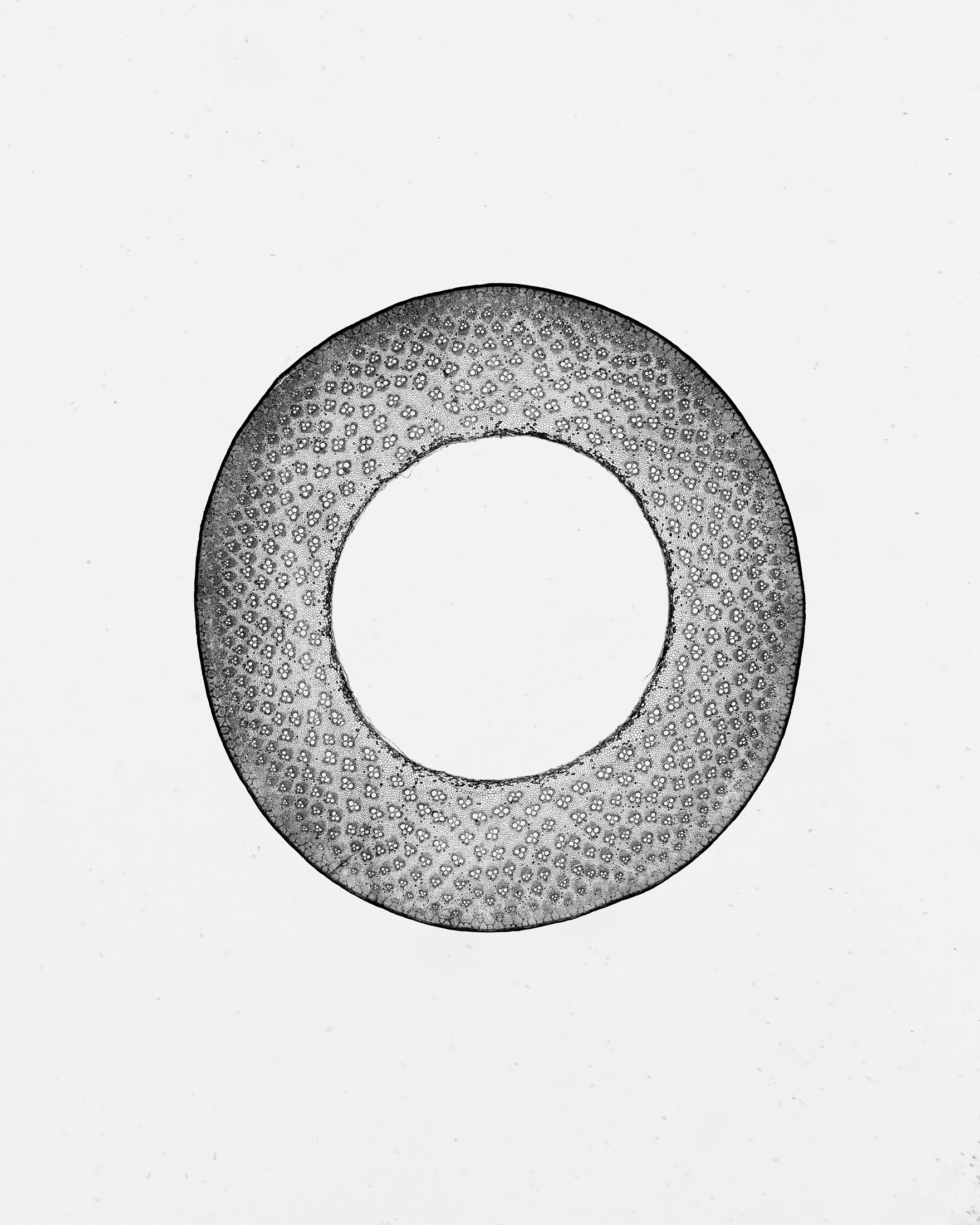

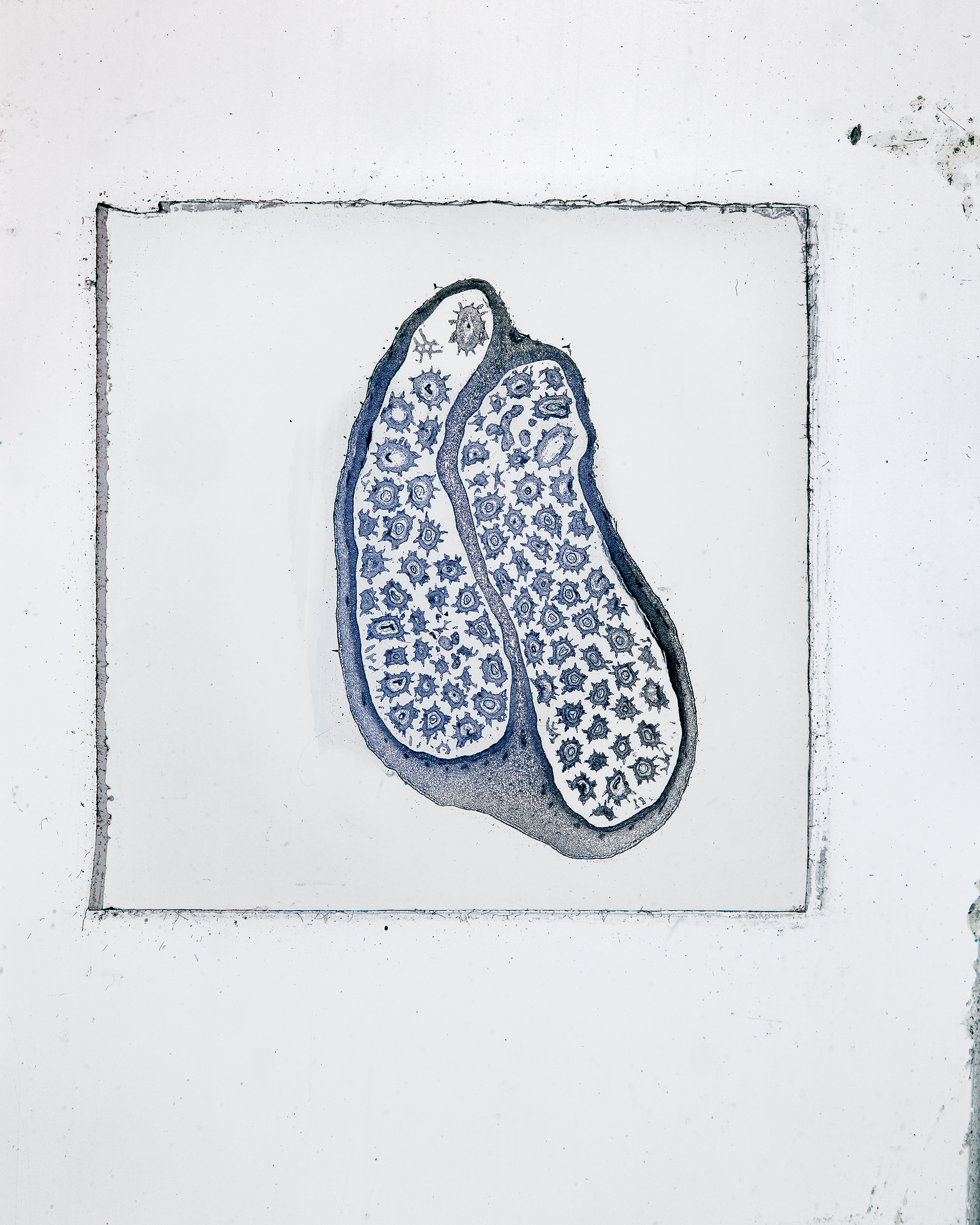

Sections, 2016-2022, archival pigment prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, dimensions variable

Sections, 2016-2022, archival pigment prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, dimensions variable, installation view: Robert Capa Contemporary, Budapest, Hungary, 2022

Photographs taken of vegetal segments on 19th-century British and French microscope slides. The segments of plants were enclosed between two glass plates before the polluting effects of the second industrial revolution and preceding motorisation, mass production and the emergence of synthetic materials. Their forms clearly refer to the species of the given plants, but at the same time they were part of a concrete living organism. Thus a segment represents not only a species but its own self, a non-human person from which they were excised. Most segments were collected from Asian, African and South American regions which were occupied and experienced violent colonisation.

Sections, 2016-2022

“We must therefore consider wherein an oak differs from a mass of matter, and that seems to me to be in this, that the one is only the cohesion of particles of matter any how united, the other such a disposition of them as constitutes the parts of an oak; and such an organization of those parts as is fit to receive and distribute nourishment, so as to continue and frame the wood, bark, and leaves of an oak, in which consists the vegetable life. That being then one plant which has such an organization of parts in one coherent body, partaking of one common life, it continues to be the same plant as long as it partakes of the same life.” John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, 1689

Pinus Sylvestris (Scots Pine), 2019 and Pinus Radiata (Monterey Pine), 2021, installation view: Robert Capa Contemporary, Budapest, Hungary, 2022

Pinus Sylvestris (Scots Pine), 2019, detail

Pinus Sylvestris (Scots Pine), 2019, archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, 102 x 127 cm

Abies Alba (European Silver Fir), 2019 and Pinus Radiata (Monterey Pine), 2021, archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, 102 x 127 cm

Pinus Radiata (Monterey Pine), 2021, detail

Drosera I and II, 2019, archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta, 122 x 152.5 cm

“What makes a person at two different times one and the same person? What is necessarily involved in the continued existence of each person over time?” Derek Parfit, Reasons and Persons, 1984

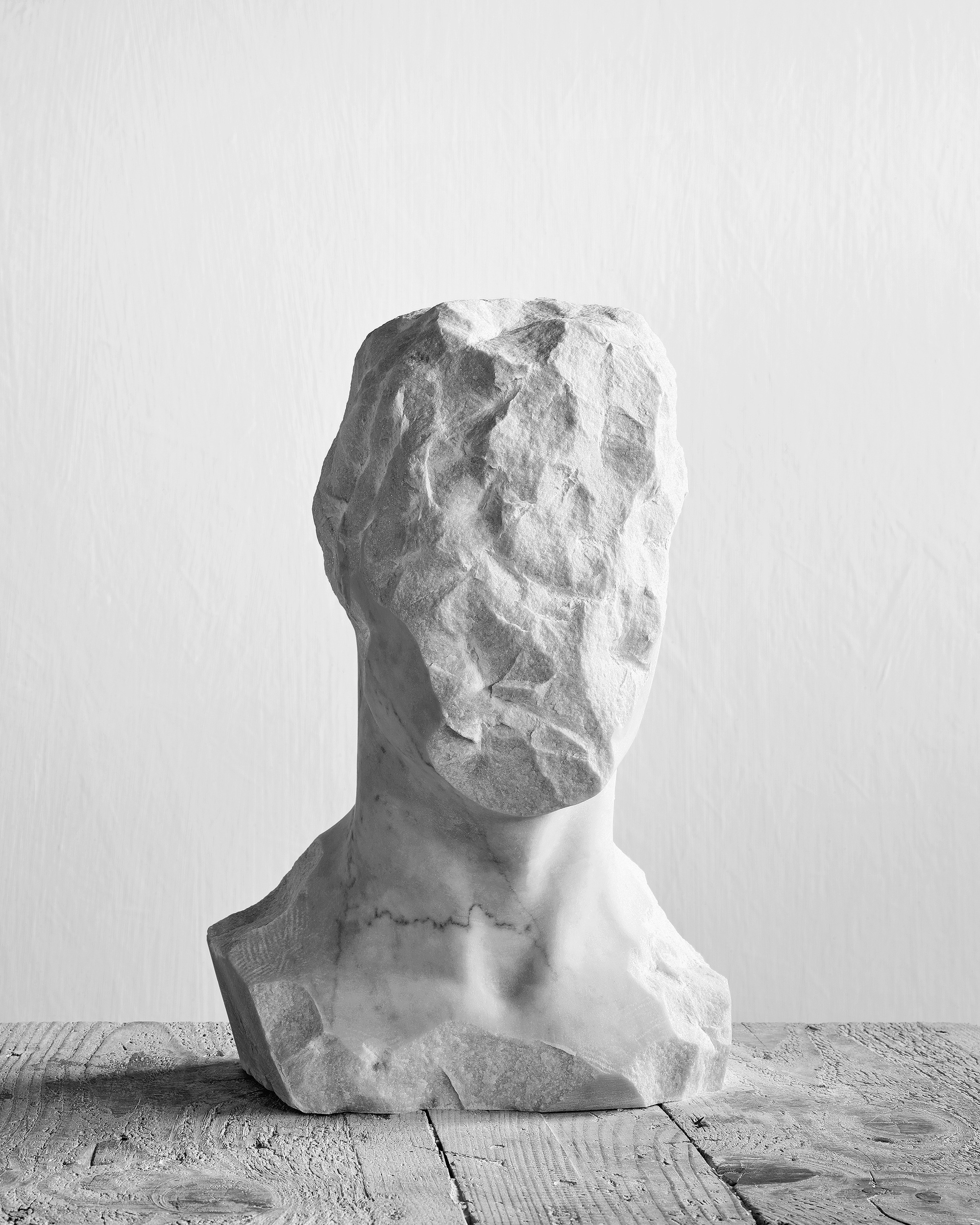

The First and the Last Variation, 2018-2022, archival pigment prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, dimensions variable

Variations on the Self, 2018-2022, installation view: Foto Wien, Atelier Augarten, Vienna, Austria, 2022

“Variations on the Self demonstrates the process-like nature of identity such that in photographs it renders the stations of carving and then disassembling the bust, and if we look at them thoughtfully the start and the end are the same. Thus we can see that the Self is not a single point, a single condition, but the totality of a temporal process from the moment of birth to death. It is a far richer, more living, variable and more open system that we imagine ourselves to be. The subject of Dezsö’s illustrative example, the model of the bust is Ludwig Wittgenstein, the sharpest and most radical critic and curtailer of the (empty) language and (false) constructions of western metaphysics.” Text by György Cséka, Hypothesis: Everything is Leaf exhibition review, A mű, 2022

Variations on the Self, 2018-2022, detail

“We like to imagine our identity as solid, constant and focused, like a core which practically stands opposite the world, the environment and nature, something which is significantly different from everything which is non-human and therefore it is obviously superior due to the mind and the ability of thinking. However this identity is purely a construction. Identity can rather be imagined as a temporal and spatial process, which permanently changes and even if we are not willing to take notice of, it is in interaction with everything it is closely bonded with and inseparable: with its world, with all the living and non-living which is not itself. There is no point whose permanence, immobility we could indicate.” György Cséka, Hypothesis: Everything is Leaf exhibition review, A mű, 2022

Garden of Persistence and Variations on the Self, installation view: Foto Wien, Atelier Augarten, Vienna, Austria, 2022, image by Zalán Péter Salát and Csaba Villányi

Vegetal and human temporality are not identical. The essence of human ontology does not originate from our life itself, but its finiteness. Plants are not aware of their own finiteness; therefore they entirely subordinate their existence to life itself. The rhythm of human time consciousness is confused and heterogeneous. In addition, human beings are actually never identical with themselves – our temporality is nothing other than continuous planning, a constant projection of our future self. In contrast, the lack of self-awareness obliges a plant to adjust exclusively to the temporality of its medium, i.e. that it should unceasingly obey the laws of its environment. The succession of night and day, the changing seasons, the constant repetition that accompany growth, the continual self-hiatus and resumption, and the rhythm of cyclic character all represent vegetative chronology, the image of Nietzsche’s eternal return (Ewige Wiederkunft). So a vegetative body exists according to a different time compared with a human body, yet its existence is still fragile and finite. Thus, we can also feel its significance. In The Metamorphosis of Plants Goethe emphasises the rhythm of growth and metamorphosis. The continual reaction to the rhythm of the environment and the flow of nutrients resemble a tune. The mechanical synchronisation of processes are like music.

Garden of Persistence, 2020-2022, kinetic table, wood, steel wire, magnets, antique metronomes, 19th century herbarium specimens, 110 x 200 x 120 cm, installation view: Foto Wien, Atelier Augarten, Vienna, Austria, 2022, image by Zalán Péter Salát and Csaba Villányi

Sections, 2016-2022, Leaf (Deutzia Gracilis), 2019 and Garden of Persistence, 2020-2022, installation view: Foto Wien, Atelier Augarten, Vienna, Austria, 2022, image by Zalán Péter Salát and Csaba Villányi

“We are not prepared to see not only mirrors and the reflection of our own constructions in the mirrors, but to see something radically and incomprehensibly different, which is itself phantomlike for us.” Text by György Cséka, Hypothesis: Everything is Leaf exhibition review, A mű, 2022

Leaf (Deutzia Gracilis), 2019, archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta, 122 x 152.5 cm

“There is no such thing as two individuals indiscernible from each other. An ingenious gentleman of my acquaintance, discoursing with me, in the presence of her Electoral Highness the Princess Sophia in the garden of Herrenhausen, thought he could find two leaves perfectly alike. The princess defied him to do it, and he ran all over the garden a long time to look for some; but it was to no purpose.” Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, letter to Samuel Clarke, 1716

Hedge, 2017, archival pigment prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, triptych, 105 x 250 cm / 130 x 320 cm, Installation view: Foto Wien, Atelier Augarten, Vienna, Austria, 2022

Antirrhinum Ovary I-II, 2020, archival pigment prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, diptych, 155 x 250 cm

All the Molds Crack, 2022, detail, glass, bronze, 70 x 30 x 30 cm

“Perhaps the most beautiful and compact metaphor of the exhibition is All the Molds Crack (2022). It comprises a glass bell, a wonderfully beautiful, translucent form created by human beings, in which a rose must have been placed, in particular a cut off, dead flower torn away from its habitat and put under the glass bell jar for aesthetic reasons. A thorn of this dead rose pierces the glass. The something that can no longer be ruled, which is no longer a purely romantic background, a field of golden age fantasies, which is no longer nature that we must save and guard from ourselves and about which we still think that its being only depends on us, breaks into our world – precisely into the consciousness of our world.” Text by György Cséka, Hypothesis: Everything is Leaf exhibition review, A mű, 2022

All the Molds Crack, 2022, detail, glass, bronze, 70 x 30 x 30 cm

All the Molds Crack, 2022, glass, bronze, 70 x 30 x 30 cm

All the Molds Crack, 2022, 70 x 30 x 30 cm, installation view: Robert Capa Contemporary, Budapest, Hungary, 2022

“Hypothesis: everything is leaf, and through this simplicity the greatest manifoldness becomes possible.” Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Notes, 1790