Everything Begins to Float

interview by Hans-Joachim Gögl

book published by Fotohof, 2025

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Do you remember any interests, talents, or experiences from your childhood that point to your current work as an artist?

As a child I was very withdrawn and shy. In social situations and even in everyday life I felt I did not fit in. Eastern Europe in the 1980s, the slow and hollow end of state socialism, intensified this feeling: not only the closed political system but its rhythm and rhetorical clichés felt alien. This was not a passing mood; it condensed into an existential stance, a durable sense of marginality that still shapes how I relate to the world. It is no accident that plant existence has become central to my artistic and intellectual interests. The voiceless, non-narrative, barely perceptible presence of plants, long outside the horizon of Western philosophy, appeared not as a passive backdrop but as an active question. In the history of philosophy, plants are often absent or serve only as metaphors. The distinctive traits of plant life, immobility, dispersed temporality, silence, do not strike me as foreign but deeply moving. In parallel with my childhood experience of outsiderness, I sense an ontological kinship with this soundless presence.

What were the most important biographical milestones in your photographic practice?

About twenty-five years ago, to overcome my social inhibitions, I turned to photojournalism and joined a daily newspaper as a photographer. I hoped that entering the world through daily interactions would dissolve my long-standing sense of being an outsider. Even when I began working for international magazines, it became clear that identity is not a role one can reshape at will, but a deeply ingrained, almost immovable structure. That realization was a turning point. I understood that I did not need to adapt so much as accept my attraction to quiet, my tendency to pay close attention, and my need for independent thinking. This is evident in my approach to photography. For me, the medium is no longer a tool for capturing the world but a space for exploring identity and inner time.

In your early work, such as Notes for an Epilogue (2010 to 2015), you examine post-communist social change in Romania. Would you agree that here photography still serves its classic purpose of reporting a quasi-objective reality?

Yes. From the outset I knew Notes for an Epilogue would close my documentary period. The decision was not a rejection of the genre but a recognition that the series allowed me to bring that phase to a coherent conclusion. It was an exceptional situation: I worked with my partner, Eszter Szablyár, then a renowned journalist, whose writing ensured depth and clarity. The resulting book is both a joint creation and a passage to a different perspective.

Due to rapid changes in digital imaging, photography has lost much of its documentary authority. How has this influenced your approach to the medium?

I never saw technological change as a threat but as a chance to expand how we think about media. Until the advent of artificial intelligence, I understood progress mainly as improved image quality. I have always approached photography through its materiality and execution, convinced that in this medium the effectiveness of the conceptual layer is closely tied to the level of technical articulation. Recent advances in digital imaging have given me the ability to render even the smallest details, which quite literally helps me, and the viewer, immerse in the image.

Your work has increasingly expanded into three dimensions, with tableaux and sculptures complementing the images. Are the large, human-scale prints meant as immersive installations rather than conventional photographic presentations?

Exactly. In recent years I have broadened my use of media, so I no longer rely exclusively on photography; the concept determines the medium in each case. This interconnection is not merely a change of form but a space for a shift in thinking. Paradoxically, this openness allowed me to reconceptualize the role of photography, which has become meaningful and relevant in my work again.

Aura, refined technique, and spaces beyond the everyday have marked your work from the beginning. Some pieces recall sacred painting or Impressionism.

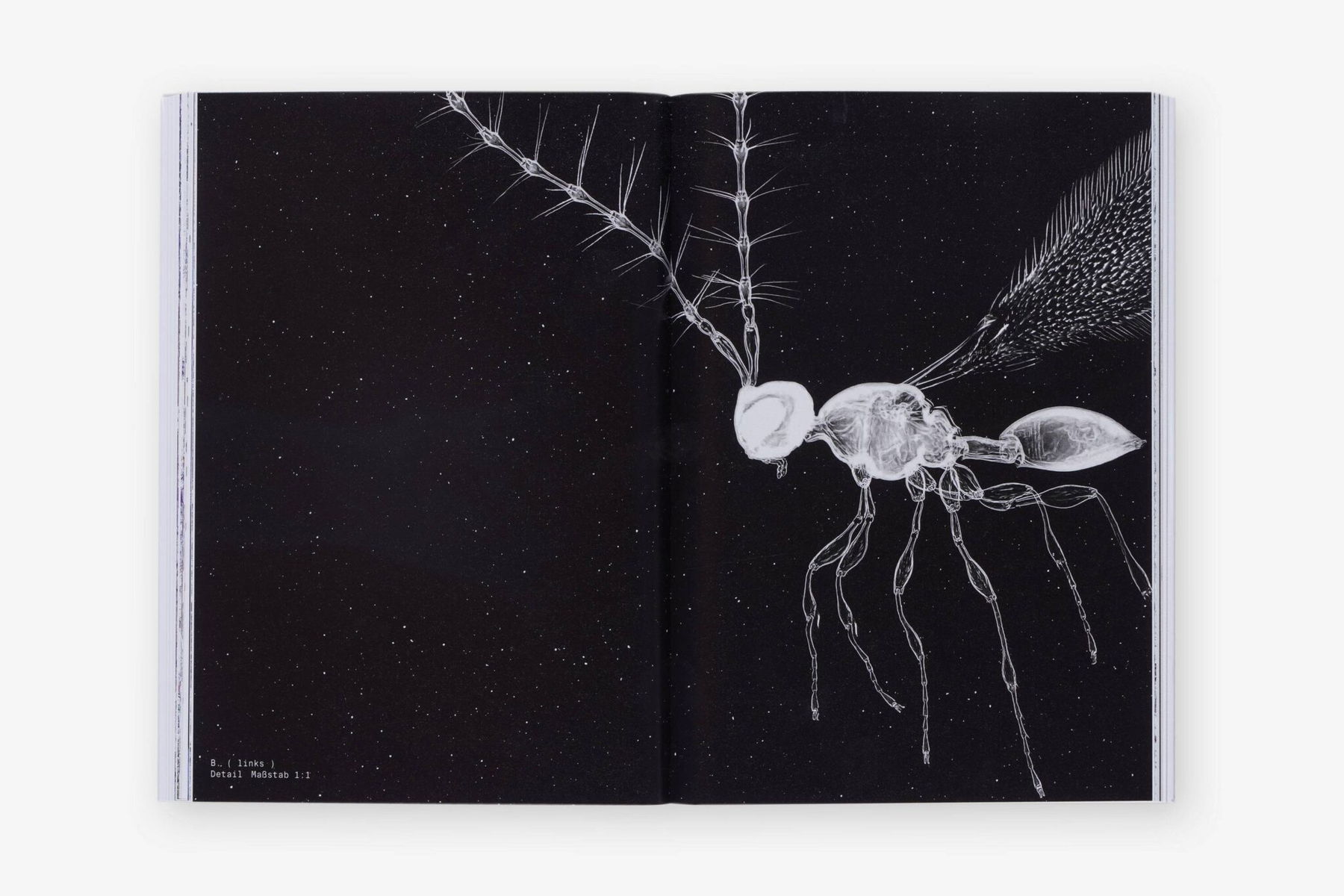

I am glad when viewers sense the intention to create iconic, quasi-sacred objects or images. This grows from my conceptual starting point, which places plant existence at the center. We are dealing with a form of life that Western thought has long relegated to the periphery of significance. Reversing that hierarchy, when the most neglected becomes most significant, is both aesthetically and philosophically rewarding for me.

Philosophy and contemporary ontological debates on reality and perception play a central role in your practice. Does theory lead practice?

Each work embodies a state of understanding or a position of thought. A significant part of my daily life is spent reading and reflecting on philosophical texts. The process is inspiring and often exhausting. When a concept takes on deeper emotional or existential weight, it prompts artistic response. A work feels valid to me when it opens an independent space for thought, one that does not merely point back to its origin but begins to exist according to its own internal logic.

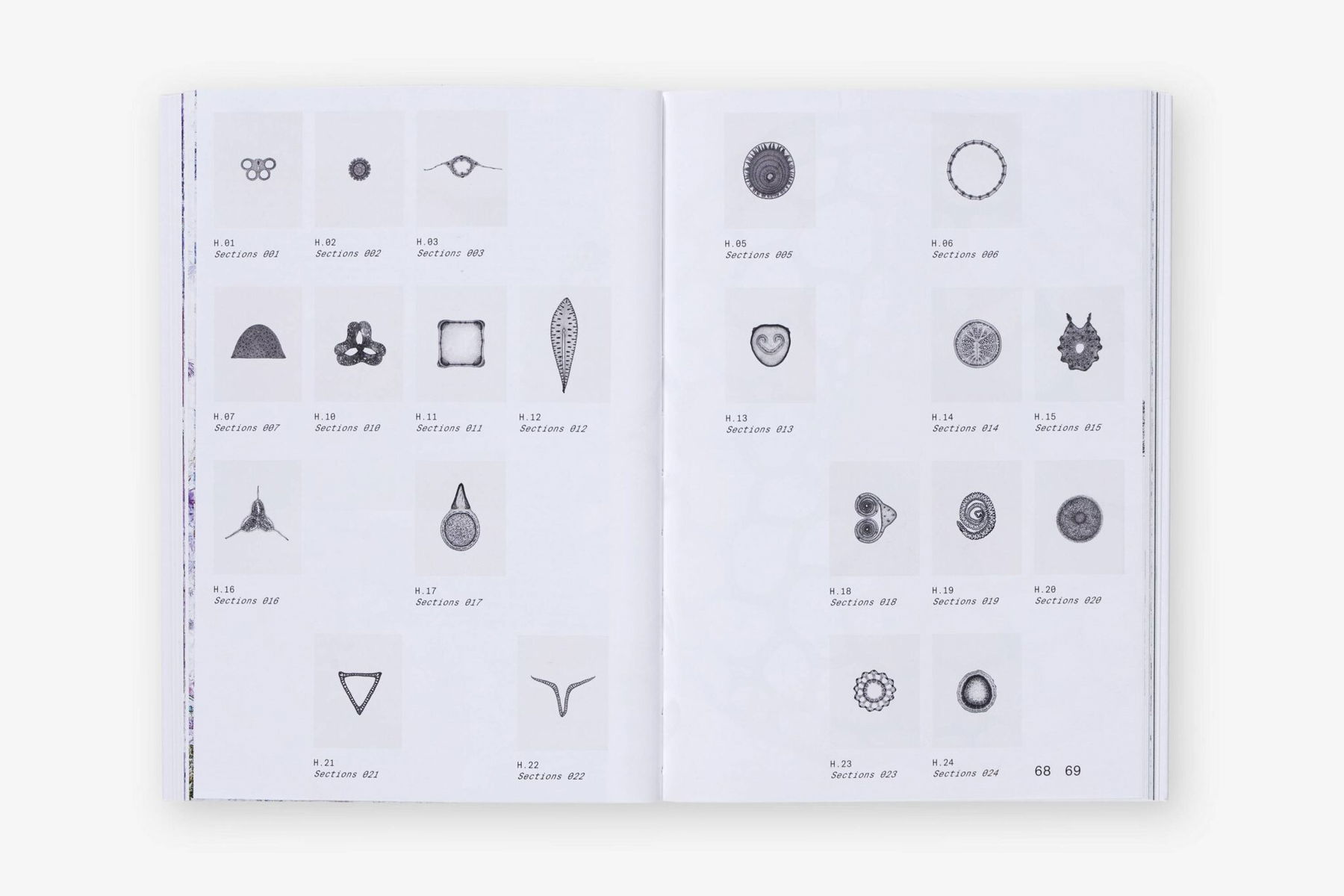

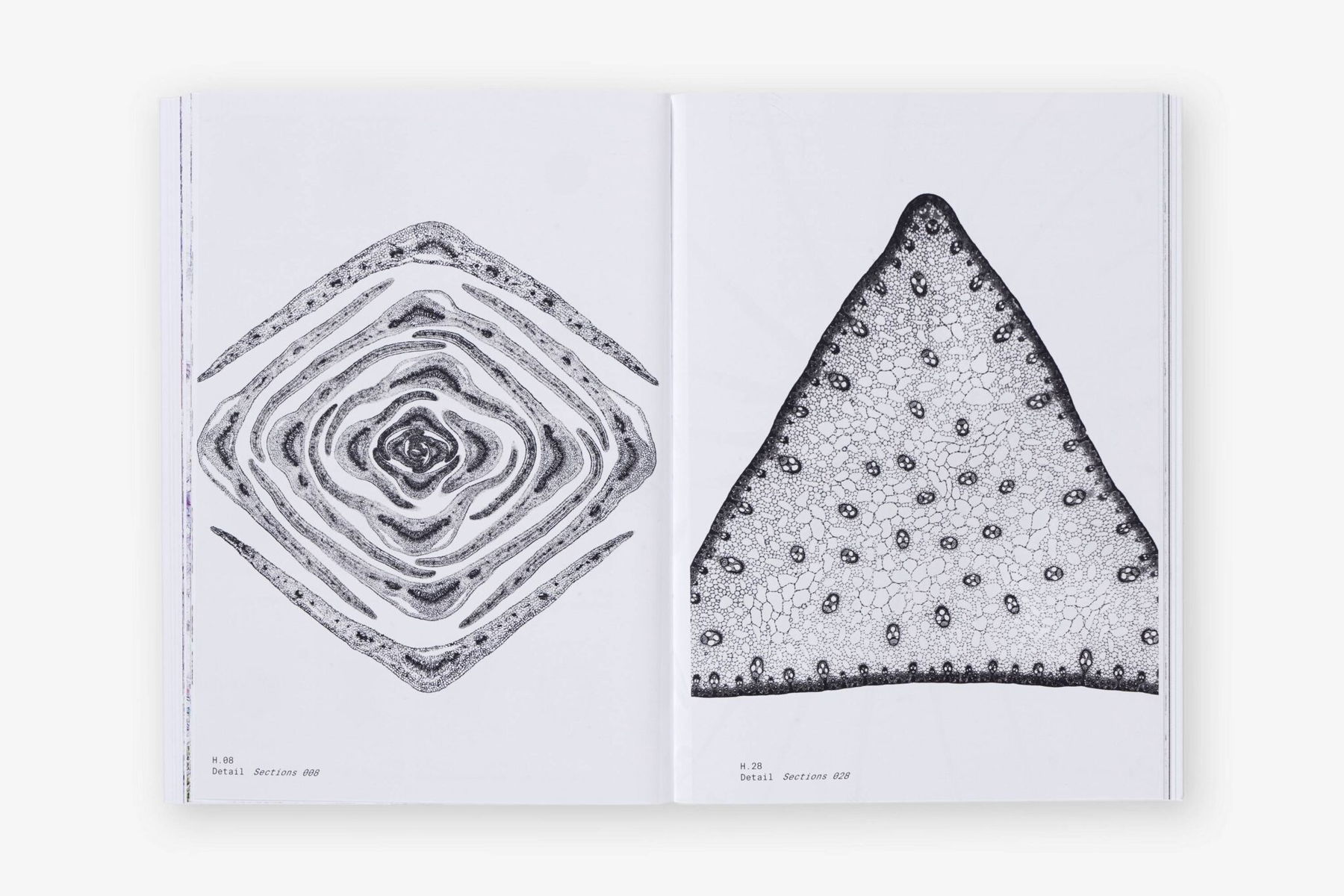

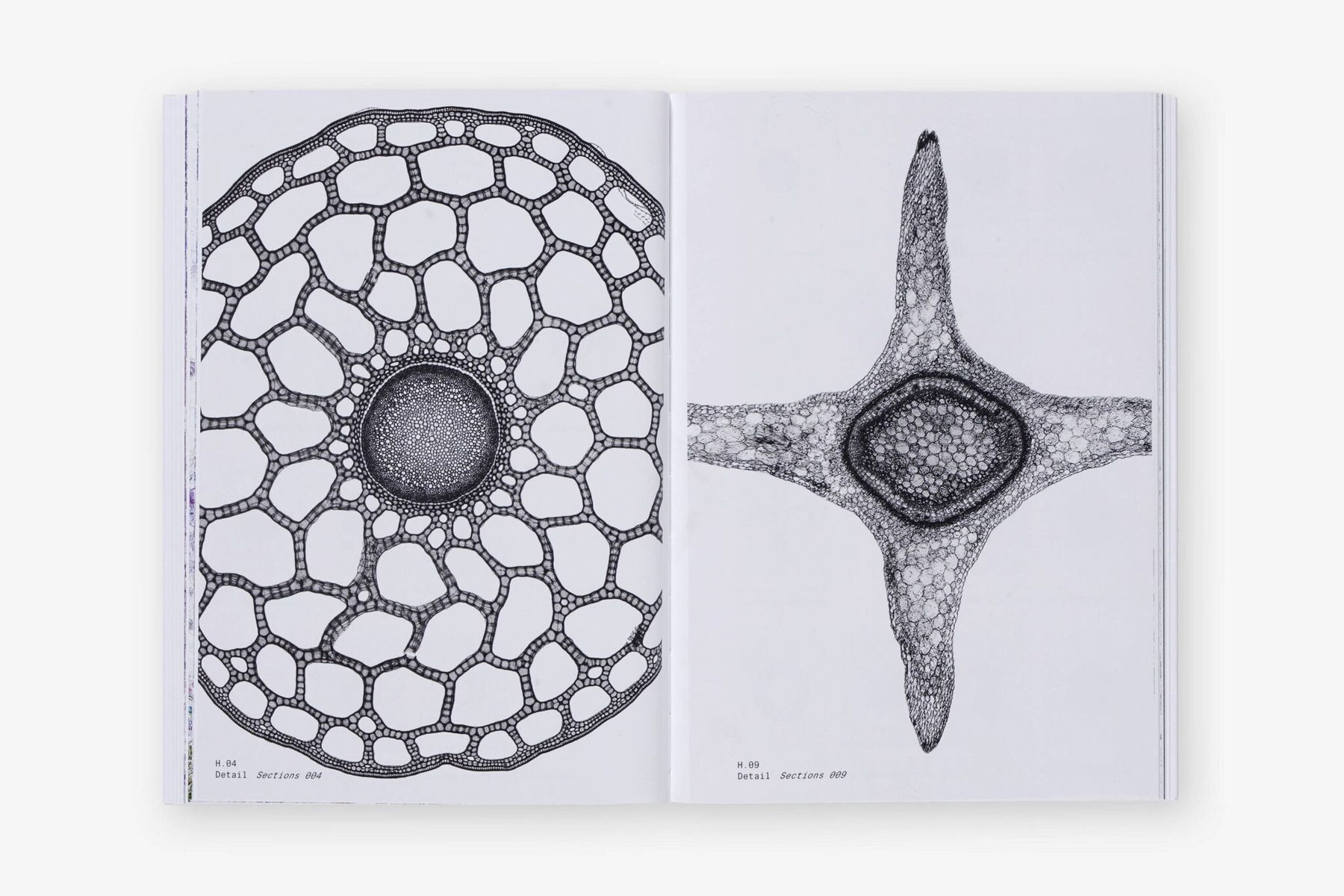

You collect historical microscope slides of plants. Is your primary interest the history of imaging techniques or the scientific study of plants?

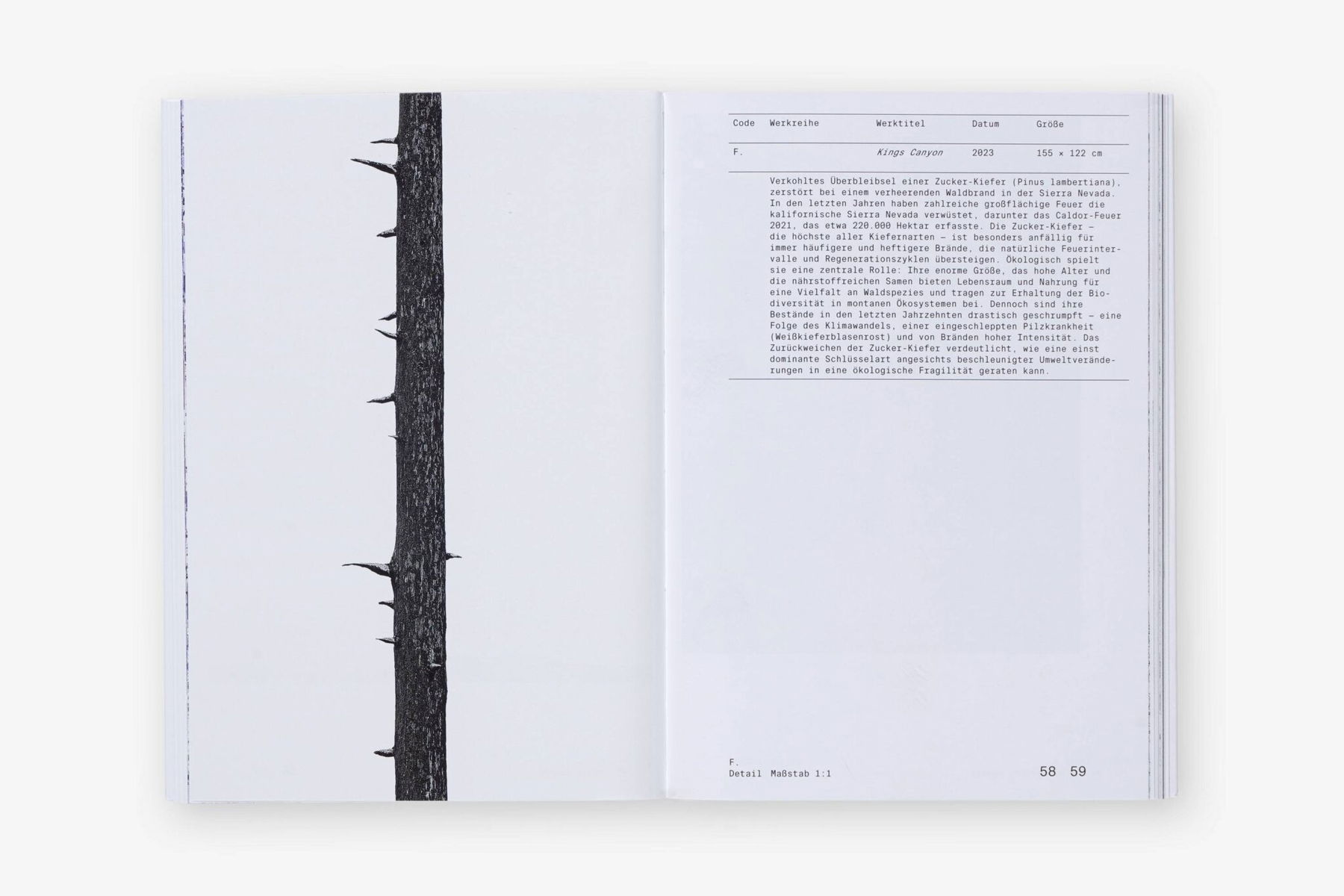

Plant existence remains a largely unexplored territory, not only conceptually but in a very concrete, physical sense. Nineteenth-century slides preserve tiny imprints of worlds beyond ordinary human perception. Looking at these fragments, we discover hidden structures and, at the same time, confront the limits of perception, the recognition that reality exceeds what we can directly apprehend.

How did you approach the INN SITU request to create a work in response to the region?

At first I struggled. I did not know the area and my temporary presence felt arbitrary. As I worked, I realized I was not asked to represent an external truth but to articulate a personal, foundational perspective: Tyrol and Vorarlberg are not closed entities but parts of the same vibrant, fragile, interconnected universe I understand as a planetary garden. Once I found this framework, the work became an inner process, less a task than a contemplative practice.

What are the main works in the exhibition and how were they created?

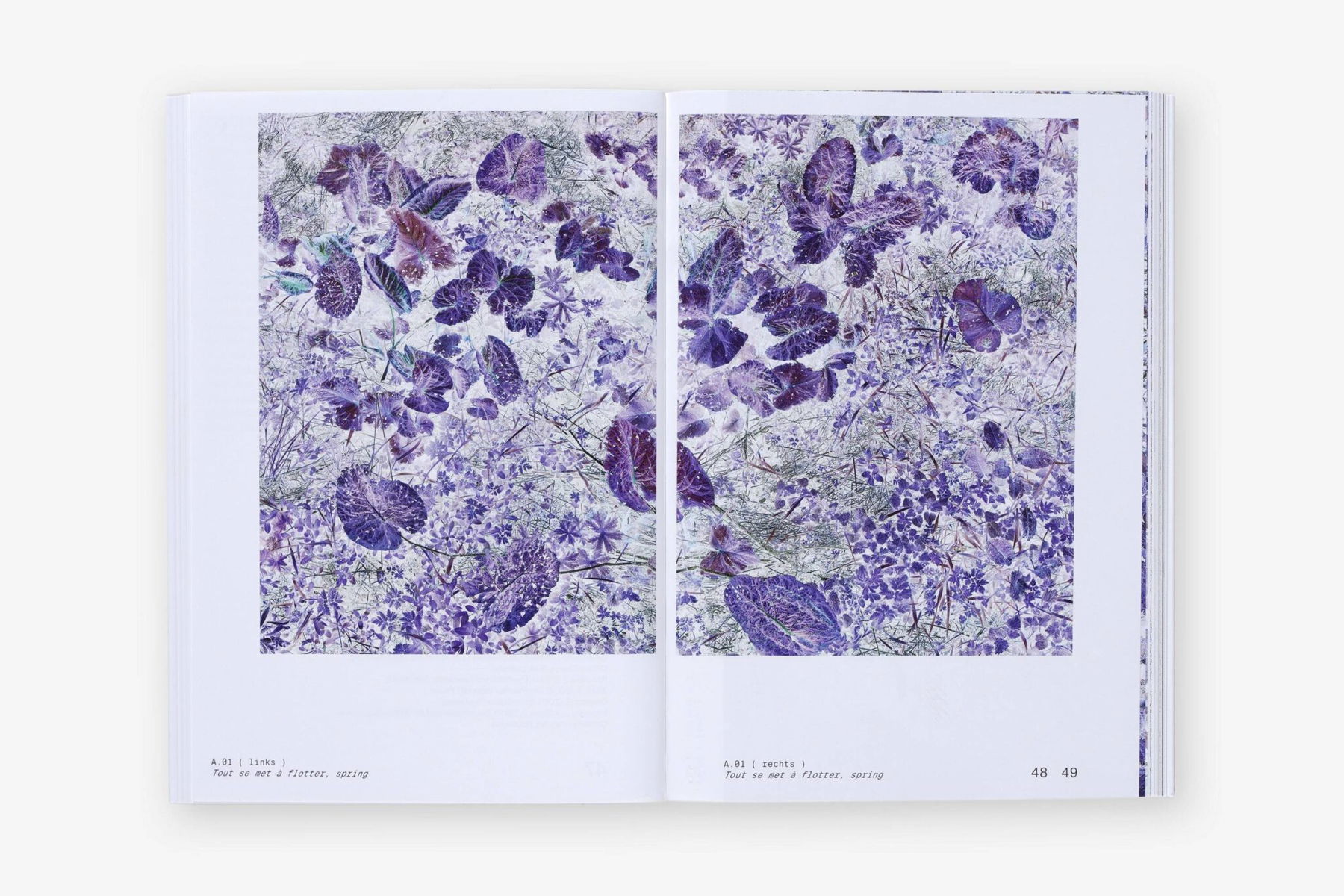

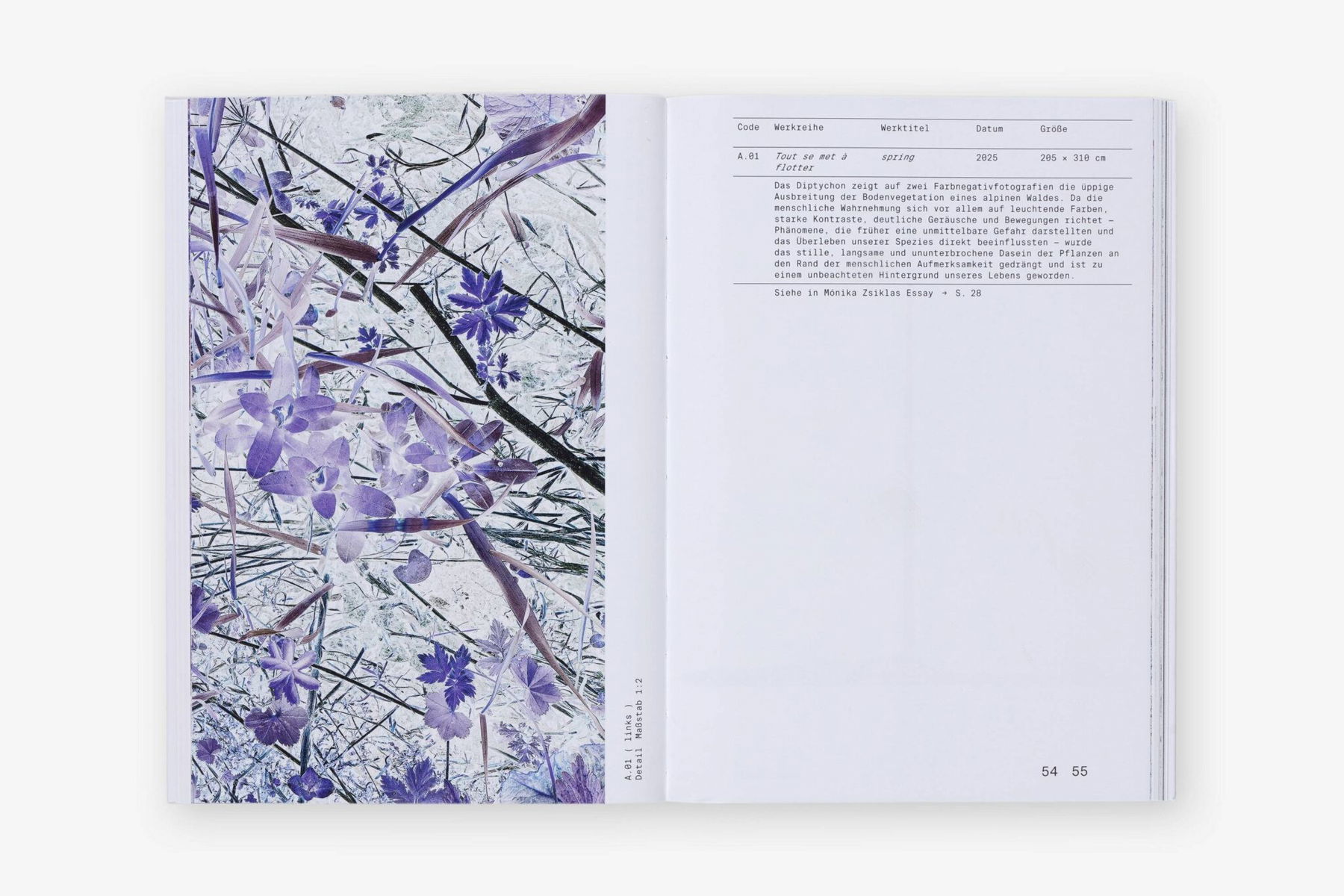

The exhibition centers on four large 2 × 3 meter diptychs made as color negatives. Created in 2024 and 2025 with a technical camera capable of extremely high resolution, the images were produced during extended fieldwork in high-altitude Alpine forests in Tyrol and Vorarlberg. The diptychs record ground vegetation without aiming at conventional representation. The negative image destabilizes familiar coordinates, suspends spatial cues, and pushes the viewer toward the boundary zone of sense-making. The photographs not only display botanical surfaces; they render tangible the decentralized, nonhierarchical, temporally structured forms of plant life. My intention is that they operate as phenomenological tools that prompt us to rethink our perceptual relations with the living environment. Other elements, sculptures, installations, smaller photographs, are arranged around this four-part axis in a relational way. The aim is not a linear narrative but an open field of interpretation where the radical differences between human and plant temporalities can emerge.

Which aspects of this exhibition are new or important for your current artistic development?

The invitation, the trust, and time in the landscape have strengthened my professional confidence. Alongside conceptual clarity and technical discipline, I found that emotional openness expands the field of interpretation. This double movement, formal rigor alongside a willingness to leave meanings open, marks a fundamental tension in my practice. In short, this region made me a little braver.

What is the significance of scenography and spatial design for you?

The effective use of space is a conceptual decision and part of the work. Here, the theme, the world and the region as a unified yet bewilderingly complex garden, strongly shapes spatial possibilities. The goal is not to enforce coherence but to build a sensory arc. I hope initial disorientation is followed by a growing sensitivity to small details, so that a new form of attachment can arise from the first strangeness. Through movement and perception, the viewer becomes not only an observer but a participant in the garden’s narrative.

What are your next goals? Which themes and strategies will you explore?

Vegetal existence and personal identity remain inexhaustible territories for me. These are not merely artistic themes but fundamental questions made urgent by current ecological and social crises. Our relation to plants is biological, existential, and vital, and its fragility is now unmistakable. At the same time, in a climate of global uncertainty, questions of personal identity press more strongly. In terms of form, installation will likely play an even greater role because it allows me to think in complex systems. It is equally important that, despite all technical transformations, photography remains part of my creative language.