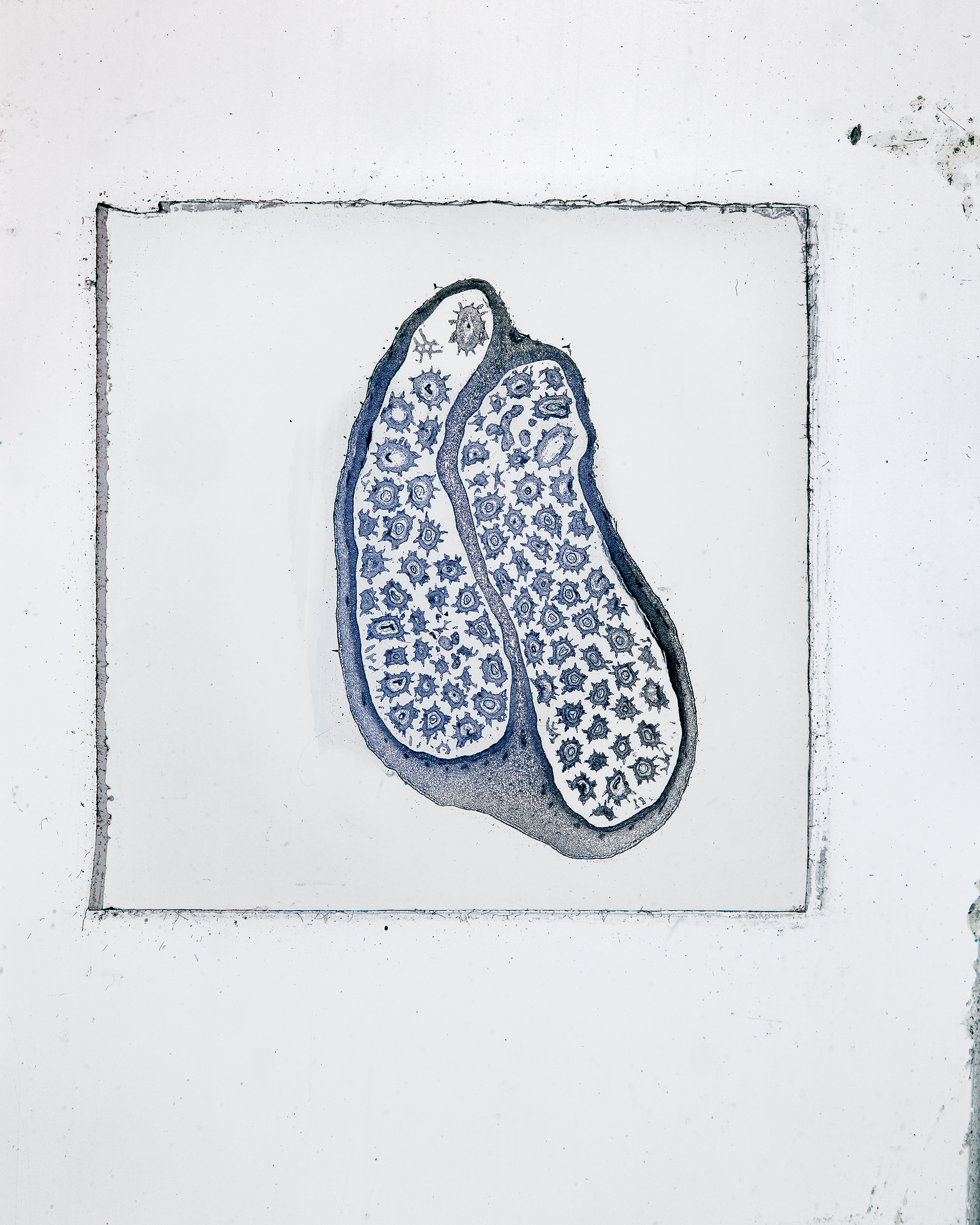

Antirrhinum Ovary I-II

2020

2020

Antirrhinum Ovary I-II, 2020, photographs taken of 19th century microscope slides, archival pigment prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, diptych, 155 × 250 cm

Antirrhinum majus (snapdragon) is a model in plant developmental genetics, showing with rare clarity how floral organ identity is set: regulators in the inner whorls govern petal versus stamen, while a separate network establishes dorsoventral patterning and bilateral symmetry. When this network fails, radially symmetrical peloric flowers appear, as early modern botanists noted. Mobile genetic elements helped map these circuits, showing that form is the outcome of layered developmental decisions rather than a given.

Because of our common ancestry, vegetal, animal, and human embryogenesis and ontogenesis share much, yet the differences matter most, especially given philosophy’s long indifference to vegetal life. Goethe’s holistic botany and his idea of vegetal metamorphosis, the archetypal leaf (Urblatt), proposed that organs arise as variations within growth. The snapdragon’s developmental switches make this visible, as organ identities retune like the modulations of a primordial leaf. Two kinds of sections on nineteenth-century microscope slides show the ovary’s chambers and the ordered array of ovules. In them, vegetal form appears as a patient, inwardly unfolding agency that points to both our shared alphabet and the plant world’s own quiet grammar.

Antirrhinum Ovary I-II, 2020, archival pigment prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta paper, diptych, 155 × 250 cm, detail